Michael M. Gunter

Introduction

The end of one year and beginning of a new one lets us reflect on what we have done and hopefully better face the future. The old year 2023 continued to see first Ukraine and then suddenly Gaza temporarily seize from the Kurds the world’s attention regarding important armed struggles. Thus, as the new year of 2024 dawns, once again it is critical to remind ourselves what is the Kurdish issue.

More than half of the approximately 35-40 million Kurds in the world live in Turkey. However, they are anything but homogeneous in their goals, ranging from those who seek assimilation into the broader Turkish society to those seeking outright independence through long-term continuing insurgency. Most of them probably would like to remain in Turkey but with guaranteed political, social and cultural rights as Kurds. However, profound regional, religious and socio-cultural differences, among others, make it difficult for the Kurds to unite. As Jonathan C. Randal, an astute Western journalist, once jocularly speculated: “I suspect a rogue chromosome in Kurdish genetics causes . . . fissiparous tendencies.”

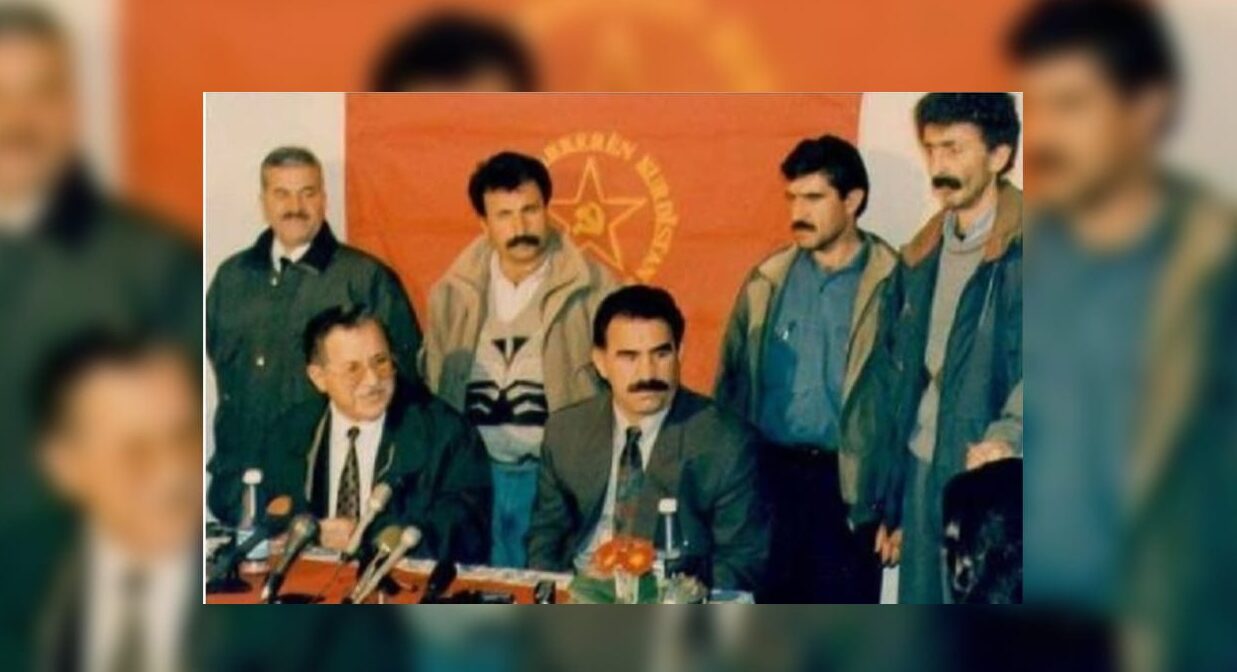

Over the years, two over-arching, seemingly contradictory themes involving change and continuity have characterized Turkey’s policy toward the Kurds. During Ottoman times (1261-1923) and even into the early Republican days, the Kurds were granted a type of separate status befitting their unique ethnic identity. However, because of the Sheikh Said Rebellion in 1925, Kemalist Turkey abruptly cancelled this policy and instead initiated one of denial, assimilation and force. The fear was that the Kurds would potentially challenge Turkey’s territorial integrity and divide the state. This apprehension proved well founded because, as detailed below, the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan (PKK) or Kurdistan Workers Party, created on November 27 1978 by Abdullah (Apo) Öcalan, launched its long-running insurgency on August 15, 1984. However, first it would be useful briefly to mention the three great, earlier Kurdish revolts.

Sheikh Said (1865-1925) was a charismatic Naqshbandi sheikh who in 1925 led the first great Kurdish revolt in the modern Republic of Turkey. After some spectacular initial successes, the vastly superior Turkish military crushed the revolt, captured Sheikh Said, and hanged him for treason. To this date, debate rages over whether Sheikh Said led a Kurdish nationalist uprising or simply one of religious reaction. In truth, both are partially valid interpretations. The explicit goal of the revolt was to establish an independent Kurdish state in which Islamic principles, apparently violated by a secular Turkey that had just abolished the caliphate, would be respected. Unfortunately for the Kurds, Sheikh Said could only rally the Zaza-speaking Kurds. Alevi Kurds actually fought on the side of the Turkish government because they felt they would be better off in a secular Turkey than in a Sunni Kurdistan led by a Naqshbandi sheikh.

The Ararat revolt (1927-1930) around Mt. Ararat in easternmost Turkey was planned by the Khoybun, a new Kurdish party based in Syria. The nationalist Armenian Dashnak Party also helped with funds. Ihsan Nuri was chosen to head a trained, non-tribal fighting force in an attempt to move away from the earlier tribal movements that had failed. A government was formed, and in the first clashes, the Kurds enjoyed some success. Eventually, however, Turkey again was able to crush the revolt because of its superior resources. In addition, Turkey obtained border modifications with Iran, which allowed Turkey to surround the Kurdish rebels and cut off their retreat into Iran.

Dersim became notorious for the third and final, major Kurdish uprising before World War II. Led by the septuagenarian Alevi cleric Sayyid Riza, the Dersim revolt lasted from 1936 to 1938 and was defeated only with the utmost scorched-earth tactics. Once again internal divisions hindered the Kurdish cause allowing Turkey to employ divide-and-rule tactics to defeat the rebels. The Alevi-speaking ethnic Kurds of the province of Dersim were not supported by Sunni Kurds who earlier had supported Sheikh Said. The name Dersim was then changed to Tunceli in an unsuccessful attempt to wipe out the memory of what had occurred. Turkey mistakenly thought that the Kurdish revolts were over.

Only gradually, beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, when this position of denial, assimilation and the fist had clearly failed with the rise of the PKK, did Turkey cautiously and incrementally begin again reversing its policy and granting the Kurds some type of recognition. Turgut Özal’s domestic and external proposals for Kurdish rights in the 1980s—although followed by Süleyman Demirel, Tansu Çiller, Bülent Ecevit, and Ahmet Sezer’s sterile return to what was essentially denialism—anticipated Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s initial domestic Kurdish Opening* but eventually failed peace process between the state and the PKK (2009-2015). As a result, a return to insurgency and counter-insurgency have been the most recent manifestations of the state’s recurring changing policy.

However, even when the state seems to be pursuing some type of peaceful recognition of the Kurds, behind this policy of change remains one of continuity, in which the state continues to see the Kurdish problem as one of security, whereas the Kurds view it as one of achieving human rights and democracy. Thus, Turkey basically offers changes only to maintain state security and its territorial integrity, not to implement change for the primary sake of Kurdish rights and democracy. The sudden explosion of the Kurdish problem in Syria because of the anarchy the civil war created there starting in 2011 has presented Turkey with a whole new dimension of the Kurdish security problem at the same time that Turkey was supposedly trying to implement change in its Kurdish dealings.

To be fair to Ataturk and his associates, their ultimate purpose, of course, was to achieve unity and modernization by mobilizing the population in Anatolia behind a territorial and civic-determined national identity. However, many Kurds perceived this attempt to be at the expense of their own religious, traditional, and ethnic identity. Indeed, a case can be made that Kemalist Turkey’s policy of attempted assimilation toward the Kurds actually made them more aware of their latent ethnic identity. M. Hakan Yavuz elaborated on the modern origins of Kurdish Nationalism in Turkey when he declared: “The state’s [Turkey’s] policies are the determinant factors in the evolution and modulation of . . . Kurdish ethno-nationalism. The major reason for the politicization of Kurdish cultural identity is the shift from multi-ethnic, multi-cultural realities of the Ottoman Empire to the nation-state model.” The Kemalist reforms, which aimed at creating a modern Turkish nation-state ironically resulted in the construction of Kurdish ethno-nationalism.

The PKK Insurgency

The PKK grew out of two separate but related sources: the older Kurdish nationalist movement that had seemingly been crushed in the 1920s and 1930s, and the new leftist, Marxist movement that had formed in Turkey during the 1960s. As Francis O’Connor, a scholar at the University of Aarhus in Denmark, wrote, “The PKK’s ten-year pre-conflict gestation period, which traversed arguably the most tumultuous period of modern Turkish history, [was] characterized by unprecedented social upheaval, violent street politics and the sadistic brutality and radical political transformation of the 1980 coup.” It was within this milieu that Abdullah Öcalan (a Turkish Kurd and former student at Ankara University) first formed the Ankara Higher Education Association (AYOD) at a Dev Genc meeting of some 7-11 persons in 1974. Öcalan told this initial meeting that since the necessary conditions then existed for a Kurdish nationalist movement in Turkey, the group should break its relations with the Turkish leftist movements that refused to recognize Kurdish national rights.

Given Öcalan’s pre-eminence, the group initially began to be called Apocular or followers of Apo. Most of the Apocular came from the lowest social classes, people who felt excluded from the country’s social and economic development. Öcalan himself was the only contemporary Kurdish national leader who did not come from the traditional elite tribal classes. In time, many other ethnic Kurds from all classes and tribes came to support and even identify with the PKK. Thus, the PKK claimed to be different from the traditional Kurdish tribal divisions and their exploitive landlords. Indeed, some of the PKK’s earliest battles were against various Kurdish tribes such as the Bucaks, whose tribal loyalties the PKK claimed prevented it from possessing a sense of Kurdish nationalism.

In 1975, Öcalan’s small group departed from Ankara and began its operations in the Kurdish areas of south-eastern Turkey. This entailed recruitment and indoctrination activities that by the late 1970s also had spilled over into violence against leftist Turkish groups termed “social chauvinists” and various opposing Kurdish groups called “primitive nationalists”. These actions helped give the group its reputation for violence. The PKK formally launched its violent guerrilla insurgency on August 15, 1984 with its famous attacks on Eruh and Şemdinli in isolated areas of south-eastern Turkey that still continues as we enter the new year of 2024.

The PKK eventually came to consist of a number of different divisions or related organizations, themselves subdivided, which operated at various levels of command in Turkey, the Middle East, Europe and even, on a lesser scale, other continents. Although there were at its best only several thousand hard-core members, tens of thousands and even several hundred thousand Kurds came to be associated with various PKK organizations and fronts. At its top, the PKK resembled the traditional model of a communist party with its undisputed leader (at various times called general secretary, chairman, or president), leadership council (in effect politburo) and central committee. The PKK also held several congresses and conferences where major policy decisions were announced.

The PKK also established a professional guerrilla army of some 10,000 fighters, the Kurdistan Peoples Liberation Army (ARGK), renamed after Öcalan’s capture in 1999, the Peoples’ Defense Forces (HPG). The Kurdistan National Liberation Front (ERNK) was a much larger popular front, which supposedly carried out political work, but also sometimes used violence. It too was formally dissolved after Öcalan’s capture, but replaced by other bodies such as the KCK. (See below.) Over the years, some of these evolved into various new groups with changing names. Furthermore, there was also a variety of sub-organs for women, youth, religious and other groups. These different groups offered the PKK useful flexibility. In addition, the PKK became adept at propaganda and journalism, publishing numerous journals and establishing the influential media outlets broadcasting throughout the Middle East, including Turkey. Finally, the PKK also established a Kurdistan Parliament in Exile, which later became the Kurdistan National Congress (KNK). The latter has been particularly active in western Europe.

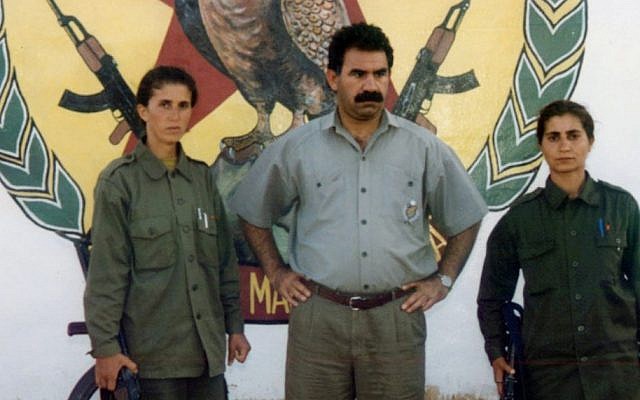

Shortly after the PKK was formally established in 1978, Öcalan had moved to Syria from where he led the party until he was finally expelled from that country due to Turkish pressure in October 1998 and captured in February 1999. Since then a small, senior group of associates including women have led the organization while still claiming ultimate allegiance to the imprisoned Öcalan.

By this time, the PKK had so ignited a sense of Kurdish nationalism in Turkey that it would be impossible for Turkey to return to the old days in which the very Kurdish existence could be denied. In addition, the PKK’s position had evolved over the years so that by the early 1990s, it was supposedly only asking for Kurdish political and cultural rights within the pre-existing Turkish borders. Turkey, however, saw this change in the PKK as insincere and felt that, if it relented even slightly in its anti-Kurdish stance, the situation would lead to the eventual break-up of Turkey itself.

Thus, the PKK insurgency represented the nightmare of Turkey’s security policy toward the Kurds and the necessity to institute a policy of counter-insurgency. One aspect of the strategy, the Village Guards, created by the Turkish government in April 1985, constitute a system of Kurdish tribes and villagers which still functions as another divide-and-rule tactic to control Kurdish insurgencies, in this case the PKK. In this respect, they were reminiscent of the Hamidiye during late Ottoman times and, more recently, the josh in northern Iraq in Saddam Hussein’s era.

Incentives to join the Village Guards included relatively good pay in an area that was chronically poor, as well as a chance to pursue ancient blood feuds with impunity, and sheer state intimidation against those who refused to participate. The most notable tribes that participated in the system were identified with the political right or already in conflict against tribes associated with the PKK. The government was also willing to use blatant criminal elements such as Tahir Adıyaman, the chief of the Jirki tribe, and at the time he was recruited, still wanted for the earlier killing of six gendarmes in 1975. Other tribes that participated in the village guards included the Pinyanish, Goyan, Bucaks, and Mamkhuran.

The PKK quickly targeted the Village Guards, resulting in some of the worse examples of the terrorism that became endemic in the south-east of Turkey. At times, both sides killed the entire families of the other. Although they eventually helped the state better control the PKK, the Village Guards were an atavistic throwback to the past in which the Turkish government placed itself in the ironic role of revitalizing feudalistic tribes, contrary to Atatürk’s supposed policies of modernity. The Turkish counterinsurgency policy also supported criminal elements as illustrated by the Susurluk scandal that broke in October 1996 and some of the abuses of the Deep State and Ergenekon. The most recently available report, from 2019, stated there were 54,000 Village Guards still operating.

Another revealing aspect of other counter-insurgency actions involved Sakine “Sara” Cansız, one of two female founding members of the PKK. In circumstances still not fully understood, Cansız was assassinated in Paris on January 9, 2013 by an apparent Turkish agent who might have been acting on rogue or “deep state” orders, not official ones. But alas, the assassin conveniently died of brain cancer on December 17, 2016 in a French prison before making any meaningful disclosures, if he even had any to offer. More than a decade later we still do not know the full tragic story.

The PKK argued that Kurdistan was a colony of the Turkish state and that only an armed struggle would bring about self-determination and national liberation. It also often protected its supporters from right-wing attacks and proactively conducted armed campaigns against certain aşiretler or tribes. In principle, the PKK viewed them as an enemy because, as already noted, in most cases they functioned as de facto representatives of the state, and were guilty of traitorous exploitation of their fellow Kurds. On the whole this proved to be a successful appeal to the PKK’s constituency. Showing its flexibility, in time the PKK also distinguished patriotic tribes from where recruits could be drawn.

Furthermore, the PKK set up communal houses where party militants would live together in order to be best able to organize movement activities. These houses became key nodes in the organization of solidarity networks throughout Kurdistan. The PKK had successfully mobilized large swathes of Kurdish society. Unlike other Kurdish movements, it breached class barriers to create a movement that encompassed all societal groups. This successful foundational labour proved key to successfully re-establishing itself after the coup in September 1980 had largely destroyed its Kurdish and other leftist opponents.

In accomplishing all this given the protracted and more cautious Maoist strategy it supposedly tried to implement, somewhat contradictorily, the PKK also followed Che Guevara’s less prudent foco strategy. This argued that armed groups need not wait for propitious structural conditions but that an armed vanguard, through its actions, can bring about the conditions favourable to weaken and eventually defeat the state. Guevara failed, but Öcalan partially succeeded. On the other hand, the PKK’s brief military venture into south-eastern urban areas of Turkey following the collapse of the Kurdish Opening peace process in 2015, was a military failure and ended in the militia’s defeat and the destruction of a number of cities. Nevertheless, the rural violence along with the endemically poor economic situation, encouraged many ethnic Kurds to move into western Turkey, to the extent Istanbul has become arguably the largest Kurdish city in the world.

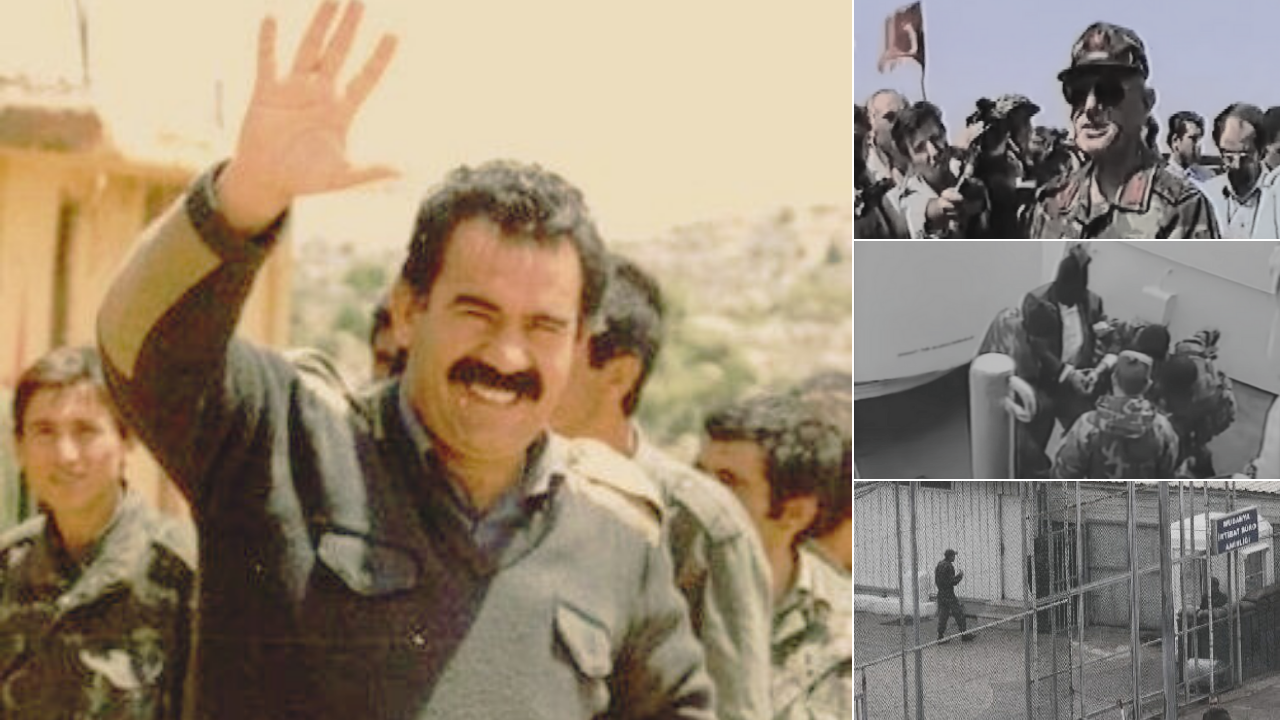

After Syria had expelled him in October 1998, Öcalan fled to Italy, where US pressure on behalf of its North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) ally Turkey pressured Italy and others to reject him as a terrorist undeserving of political asylum or negotiation. Indeed, for years the United States had given Turkey intelligence training and weapons to battle against what it saw as the “bad” Kurds of Turkey, while ironically supporting the “good” Kurds of Iraq against Saddam Hussein. With US and possibly Israeli aid, Öcalan was finally captured in Kenya on February 16, 1999, flown back to Turkey for a sensational trial and sentenced to death for treason.

However, instead of making a hardline appeal for renewed struggle during his trial, Öcalan issued a remarkable statement that called for the implementation of true democracy to solve the Kurdish problem within the existing borders of a unitary Turkey. He also ordered his guerrillas to evacuate Turkey to demonstrate his sincerity. Thus, far from ending Turkey’s Kurdish problem, Öcalan’s capture began a process of implicit bargaining between the state and many of its citizens of Kurdish ethnic heritage as represented by the officially illegal PKK and various legal pro-Kurdish parties such as the Barış ve Demokrasi Partisi (BDP), or Peace and Democracy Party, which was created after the Demokratik Toplum Partisi (DTP), or Democratic Society Party, was banned on December 11, 2009, but was subsequently merged into the more inclusive Halkların Demokratik Partisi (HDP), or Peoples Democratic Party, in April 2014. After the elections in May 2023, the Halkların Eşitlik ve Demokrasi (HEDEP)* or Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party replaced the HDP, which faced being banned. Since the 1990s, these legal pro-Kurdish parties have elected numerous mayors in the Kurdish areas during the local elections, next scheduled for March 31, 2024. (However, the state has replaced many of these legally elected Kurdish mayors, with state-appointed trustees willing to do the state’s bidding.) Kurds also gained representation in the Turkish parliament running first as independents, but since 2015 as a party.

Arguing that Turkey had not implemented the necessary reforms, the PKK ended the cease-fire it had implemented after Öcalan’s earlier capture in March 1999 and renewed low-level fighting in June 2004. In addition, opposition to Turkish membership in the European Union (EU) began to grow, especially in such EU members as France, Germany, and Austria, among others. In November 2002, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP), or Justice and Development Party, with its roots in Islamic politics, won an overwhelming victory, which it added to in subsequent elections held in July 2007 and June 2011. In August 2014, Erdoğan was also elected president, the first time that office was chosen by a popular vote instead of by the parliament. Subsequently, Erdoğan’s AKP won new national elections in 2015, 2018, and again in 2023. Despite the Gezi Park demonstrations of June 2013 against perceived authoritarian AKP rule, the so-called Gülenist coup attempt in July 2016, serious charges of corruption, and a steadily deteriorating economy, Erdoğan remained in power as of this writing in early 2024.

Beginning in 2005, the Koma Civakên Kurdistan (KCK), or Union of Kurdistan Communities had begun to operate as the umbrella organization bringing together the PKK and numerous other related Kurdish groups in Turkey as well as in other states in the Middle East and Western Europe. Under the leadership of first Murat Karayılan and after July 2013 Cemil Bayık, and Bese Hozat—implementing the co-leadership principle of having a male and female supposedly share the position, a leadership principle foreign to most Middle Eastern societies —approximately 5,000 PKK guerrillas remained entrenched in the Qandil Mountains straddling the border between northern Iraq and Iran. Subsequently, the guerrillas have also spread to the Sinjar region in north-western Iraq, first to combat ISIS, but remaining thereafter. Their number has also grown. The situation has drawn Turkish armed forces to attack them.

Rise and Fall of the Kurdish Opening

During the summer and fall of 2009, the continuing and often violent Kurdish problem in Turkey briefly seemed on the verge of a solution when the ruling AKP government of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and President Abdullah Gül announced a Kurdish Opening or Initiative (aka as the Democratic Opening/Initiative). However, Erdoğan was first and foremost an adept politician. Thus, his main purpose has been to maintain and even expand his electoral mandate. In so doing, he has many opposing constituencies to appease and satisfy. If he went too far in satisfying the Kurds, he would surely alienate other, larger Turkish nationalist elements of the electorate. As a result, Erdoğan seems to have treated the mere agreement to begin the peace process as the goal itself, rather than as a part of a process to address the root causes of the conflict.

The continuing civil war in Syria interjected this new security dimension as a further factor into the problems of the peace process. De facto Kurdish autonomy just across the Turkish border in Syria’s Hasakah (Jazira) province played havoc with Turkey’s fears regarding what it perceived as the PKK threat. The problem was even greater because the leading Kurdish party in Syria was the Partiya Yekitiya Demokrat (PYD) or Democrat Union Party, originally an affiliate of the PKK, but now an autonomous ally. In effect, this meant that, even though the PKK was supposed to be withdrawing across the border into Iraq’s Qandil Mountains, it now had extended its cross-border presence next to Turkey by several hundred miles in Syria. This new Syrian position granted the PKK a type of strategic depth that added to its influence.

Turkey reacted to this situation by bitterly opposing the PYD politically and diplomatically and also covertly supporting armed Jihadists/Salafists mercenaries and groups such as Jablat al-Nusra which was affiliated with al-Qaeda, and the even more extremist Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which even al-Qaeda had disowned. Although since January 28, 2017, Jablat al-Nusra has joined with others to form an apparently less radical group known as the Hayat Tahir al-Sham (HTS) or Organization for Liberation of the Levant, the HTS enjoys continuing Turkish support against Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian government, its Russian ally, and the Syrian Kurds. These Salafists/Jihadists looked upon both the Assad regime and the secular Kurds as Takfiri or apostates. Bitter fighting broke out between them and the Syrian Kurds, largely led by the PKK-affiliated PYD. Soon Turkey found itself in the unenviable position of seemingly siding with al-Qaeda-affiliated Salafists/Jihadists fanatics against secular, even pro-Western Syrian Kurds. This had become all the more apparent when Turkey disdained to join the United States-led coalition against ISIS during the bitter fighting in Kobane, Syria, during September 2014-January 2015.

Turkish Counterinsurgency Operations

How would Turkey react to a growing Kurdish entity associated with the PKK on its southern border in north-eastern Syria? In addition, of course, what would happen once Assad inevitably began to reimpose his authority? When it ended its Kurdish Opening in the summer of 2015, Turkey began to reply to this query with a series of counter-insurgency campaigns starting with Operation Euphrates Shield in 2016 that successfully prevented the Syrian Kurds from crossing west of the Euphrates River to unite with the isolated Kurdish canton of Afrin (Kurd Dagh). Then in 2018, another Turkish counterinsurgency dubbed Operation Olive Branch conquered Afrin and thus eliminated this perceived threat. Finally, a Turkish counterinsurgency drive in October 2019 entered portions of north-eastern Kurdish Syria east of the Euphrates River when the United States pulled most of its support for the Syrian Kurds.

U.S. President Donald J. Trump’s decision to pull out some 1,000 U.S. troops acting as advisers, supporters and protectors of the U.S. proxy, PKK-affiliated Democratic Union Party/Peoples Defense Units / Syrian Democratic Forces (PYD/YPG/SDF), which also included the Womens’ Defense Units (YPJ)—altogether simply the Syrian Kurds—facilitated the Turkish incursion. Despite the efforts of Mazloum Abdi, the overall SDF/YPG/YPJ commander and former PKK member, this new Turkish counter-insurgency allowed Turkish forces and its mercenaries to carve out an enclave for themselves 20 miles deep, and stretching approximately 75 miles along the Syrian-Turkish border between the cities of Tel Abyad and Ras al-Ayn to add to their earlier counterinsurgency operations. Turkey again claimed to fear supposed Kurdish threats to its southern borders.

However, a reduced U.S. military presence still remained, presenting the appearance of a modicum of continuing U.S. protection. Earlier, in August 2014, the United States actually worked indirectly with the PKK by giving it air support in its battle to protect the heterodox Yazidis in Sinjar (Shengal) from the genocidal assault by ISIS. The United States was so impressed by the PKK’s military ability and that of its Syrian associates the SDF/PYD/YPG that a tacit alliance against ISIS soon developed, much to the chagrin of Turkey. Michael Knights and Wladimir van Wilgenburg have ably analyzed this de facto alliance in their recent book entitled Accidental Allies: The U.S.—Syrian Democratic Forces Partnership Against the Islamic State, first published in 2022.

By 2022, Erdoğan was again arguing that it was necessary for Turkey to carry out further counter-insurgency strikes against the perceived Syrian Kurdish enemy which he saw as facilitating the continuing PKK insurgency. However, Russia (over its head in its new war in Ukraine), Iran and the United States, a motley grouping if ever, opposed Erdoğan’s proposed fresh incursion into Syria.

At the same time Turkish counter-insurgency operations were taking place in northern Syria against the Kurds, fighting was also occurring in northern Iraq, indeed had been intermittently since the 1980s. This fighting now escalated for a variety of reasons. The main PKK bases since being ejected from Syria in 1998 have been in the Qandil Mountains of northern Iraq near the Iranian border in the east. However, in 2014, the PKK also moved guerrillas to the Shengal (Sinjar) region of northern Iraq about 100 miles from the Turkish and Syrian borders in the west. As noted above, this was to save the Yazidis from the genocidal onslaught of ISIS. Successfully accomplished, the PKK remained in the region, a situation that greatly troubled Turkey.

Beginning in mid-2019 new Turkish Operation Claw counter-insurgency operations now expanded to carve out a more permanent “security belt” instead of merely withdrawing after a brief incursion. The new counter-insurgency goal was to deny the PKK the capacity to operate, organize, train, recruit or attack within and from its “security belt,” and secure the border security of Turkey. With occasional support from the Barzani-controlled Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq (also known as southern Kurdistan or Başur), Turkey was seeking to dislodge a strong PKK presence in Shengal as well as other PKK targets situated in the mountainous areas of Metina, Zap and Avashin-Basyan in Duhok province well west of the original PKK bases in the Qandil Mountains. The PKK claimed that the Turkish operations were only possible with the support of the KRG.

On February 14, 2021, in a bunker cave on Gare Mountain, Turkish troops discovered during Operation Claw-Eagle 2 the bodies of 13 Turkish citizens who had been captured earlier by the PKK. Both sides accused the other of being responsible for the deaths. A year later on April 18, 2022, Turkey launched Operation Claw-Lock, the fourth stage of its Claw operations, driving about 65 miles into northern Iraq with over 4,000 soldiers and setting up more than 100 military outposts and five bases against entrenched PKK guerrillas. Both sides claimed to inflict heavy casualties on the other. The PKK also repeatedly charged that the Turkish military used chemical weapons in this fight and that it had responded with a wide range of tactics, such as ambushes, infiltrations, raids, sabotage, assassinations, the use of heavy weapons, ‘hit and run’ actions, coordinated guerrilla actions, air defence force actions and revolutionary operations. Iraqi Kurdish civilians also suffered both the destructions of their homes and deaths. In a particularly egregious incident on July 20, 2022, Turkish bombing also killed nine Iraqi Arab civilians vacationing in Parakh, a hill village in the Duhok governorate of the KRG. Although Turkey incredulously blamed the attack on the PKK, the Iraqi government accused Turkey and even warned that that it reserved the right to retaliate.

Conclusion

According to the scholar Francis O’Connor cited earlier, “Öcalan seems to genuinely believe that he possesses qualities beyond those of other members of the movement and Kurdish society.” However, “the application of these strategies on the ground was necessarily far removed from Öcalan’s idealised plans whose complete lack of experience as a guerrilla fighter led him to impose unworkable demands upon his field commanders.” Continuing, O’Connor writes, “In admittedly simplified terms, strategic developments which led to positive outcomes are attributed to Öcalan and other strategies which were less successful are blamed on others within the movement or on their incorrect implementation of his instructions.”

Even before the PKK insurgency actually began, wrote O’Connor, “Öcalan was based in Syria while the PKK guerrillas were located inside the borders of Turkey, often in isolated rural areas.” As O’Connor notes, “this emphasizes the distinction between how conflicts are idealised at the centre and realised in the periphery.” The strategic implications of this on the PKK’s success since Öcalan’s capture in 1999 are important to consider. Indeed, one might make a strong case that the PKK has proven more successful with Öcalan removed to the role of only a titular leader. His everyday return might jeopardize actual continuing success now implemented!

Thus, the PKK’s continued persistence and relative success may ironically depend on Öcalan’s continuing incarceration. If freed, would the current PKK leadership really accept his renewed leadership? I doubt it. Indeed, an imaginative Turkish state policy might be to free the titular PKK leader and cause a leadership rift in the party. Continuing with these speculations, would the PKK have come as far as it now has with Öcalan as its actual rather than imprisoned titular leader? Probably not. Would today’s China be in its present strong economic and therefore military and political position if Mao Zedong had somehow continued to live and rule instead of dying in September 1976? I think not. It took Deng Xiaoping to bring China into the modern era and so it has with the PKK although I do not know if I can identify just one PKK leader among the several who did it. Maybe what we have here is an example of a rare, successful collective leadership more dedicated to the Kurdish cause than their own personal glorification and furthered by the principle of dual gendered leadership so foreign to most Middle Eastern societies.

Yet today, the PKK ultimately still suffers from what elsewhere I have called “the bane of Kurdish disunity”, manifested today by the deadly fighting in northern Iraq between it and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). This situation clearly allows Turkey to play the two Kurdish entities off against each other with divide-and-rule tactics. What kind of future is this? What should we make of the continuing disunity? Pan-Kurdish unity would seem unlikely.

Yet today, the PKK ultimately still suffers from what elsewhere I have called “the bane of Kurdish disunity”, manifested today by the deadly fighting in northern Iraq between it and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). This situation clearly allows Turkey to play the two Kurdish entities off against each other with divide-and-rule tactics. What kind of future is this? What should we make of the continuing disunity? Pan-Kurdish unity would seem unlikely.

If there are 22 Arab states in the world, why not at least two Kurdish ones? Given their common Ottoman past and maybe even the more relevant fact that many Syrian Kurds originally arrived from there following the failed Sheikh Said rebellion in Turkey in 1925 and thus still have strong roots in Turkey (the late, famous Syrian Kurdish scholar Ismet Cheriff Vanly is an excellent example), one Kurdish state might be created by the leftist Turkish PKK in Turkey (Bakur) with its allied PYD, the ruling Kurdish party today in North and East Syria (Rojava). However, the entire question of a PKK state continues to run aground on existential Turkish opposition. The other Kurdish state is clearly the more politically traditional, Barzani-led KRG (Başur). In addition, Iranian Kurdistan (Rojhilat) constitutes yet another factor in this speculation.

In conclusion, it would be revealing to compare the Taliban’s ultimate success in Afghanistan with the PKK’s lack thereof. The answer clearly lies in the continuing prowess of the Turkish government and its military compared to the ineptitude of Afghanistan’s. This would suggest that the PKK strategy must consider and respect the staying power of its state opponent and seek some ultimate solution less than a traditional guerrilla victory. On the other hand, given the PKK’s proven persistency, Turkey cannot anticipate a Sri Lankan solution of completely eradicating the insurgents. Welcome to the continuing challenges of a new year!

Michael M. Gunter is a professor of political science at Tennessee Technological University, the author of 23 scholarly books, and more than 150 peer-reviewed, scholarly book chapters and journal articles. The opinions expressed in this article are solely his views, not those of others.

* Editor’s notes: 1- The writer uses Kurdish Opening, a translation of the Turkish language term Kürt Açılımı to describe 2013-2015 peace process, or solution process, between Turkey and the PKK, a period of truce which started in 2013 but collapsed in 2015. 2- Since this article was written, the acronym HEDEP used for the Peoples’ Democracy Party has been banned in Turkey, and has been replaced by the acronym DEM Party.