Erling Folkvord

War is often a necessary part of the liberation struggle. War in itself does not provide a solution, but it can force negotiations. Political negotiations can then gradually lead to a solution and a process of reconciliation. The chances of reconciliation are best if the liberation movement holds onto its weapons until a stable political solution is in place – however, if they give up their weapons during the process, things rarely go well.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s view of Palestinians, as broadcast on TV daily, is the same as the view Turkey’s president has of Kurds. To summarize the core of Netanyahu’s message: they must be exterminated if they do not give up their own culture and identity and accept the dictatorship of the oppressor.

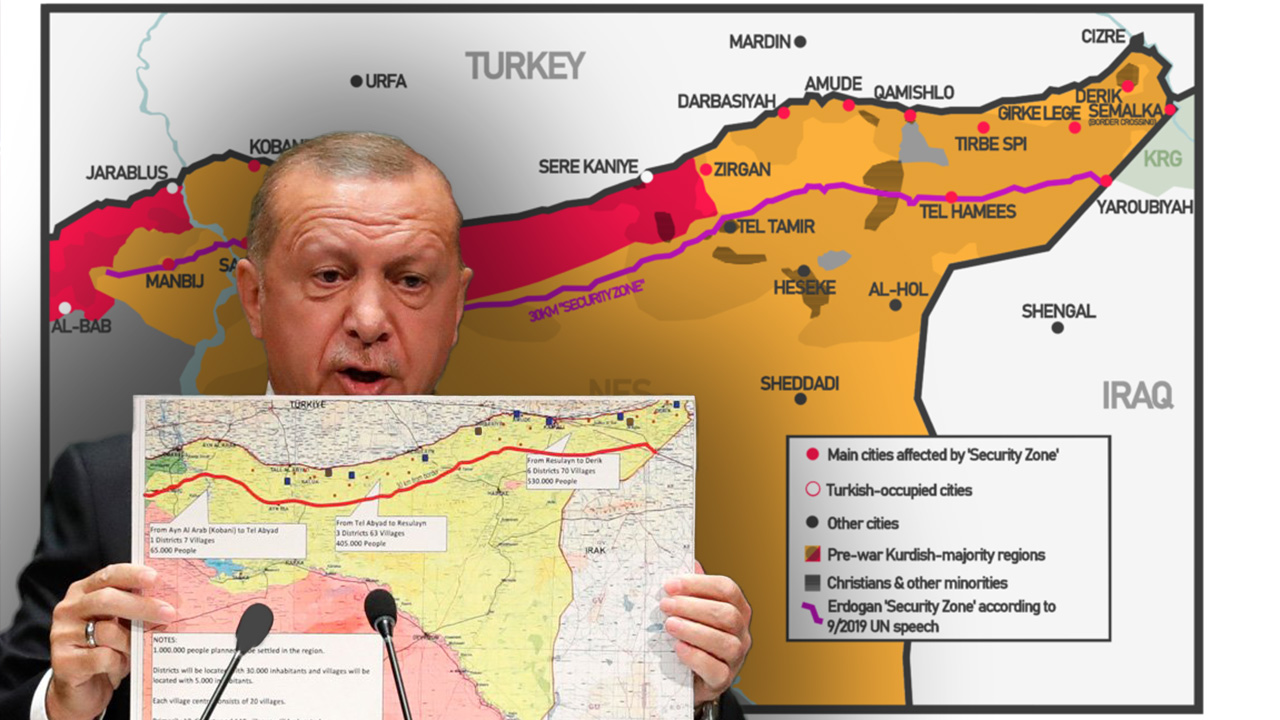

Turkish President Erdoğan does not speak as clearly as Netanyahu does. But through terror, war and displacement of people, Erdoğan has shown every day that this is exactly what he stands for.

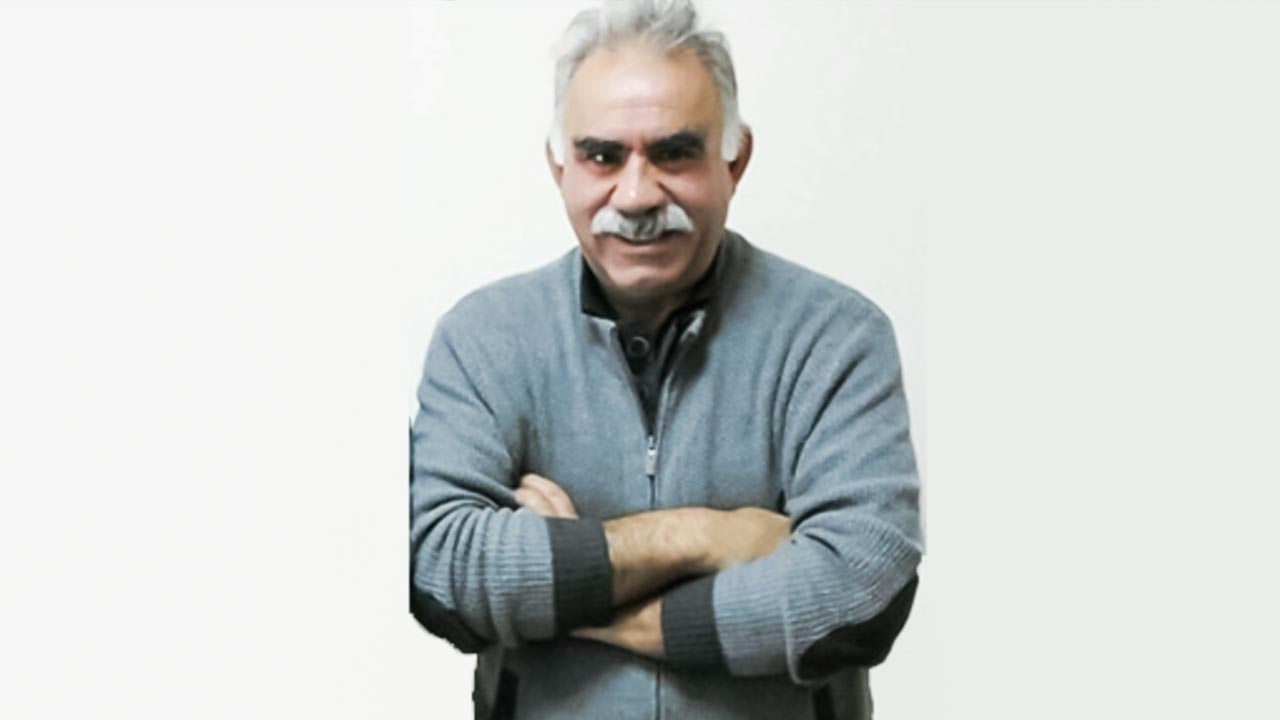

It has now been just over 25 years since Turkey announced an invasion of Syria if Abdullah Öcalan did not leave the country. A few months after that announcement, CIA agents kidnapped Öcalan from the Greek embassy in Kenya. Next, they handed him over to Turkish Intelligence Agency (MİT) agents who had been waiting at the airport. MİT’s efforts were limited to flying Öcalan to Turkey after the CIA had done its job – showing further proof of the Turkish government’s inferiority.

2013: The Newroz appeal

But this didn’t break Öcalan or the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). On Newroz Day, 14 years after his abduction by the CIA, Öcalan issued a peace appeal from his prison cell in Imrali. He addressed all the people of the Middle East, not just the Kurds:

“The era of exploitative regimes, oppression and denial is over. The people of the Middle East and Central Asia are waking up. They are returning to their roots. They are demanding an end to the blinding and subversive wars and conflicts that pit them against each other. (…) Today begins a new era. The time of armed struggle is ending and the door is about to open for democratic politics.”

The massive support for this Newroz appeal must have made an impression on the Turkish state leadership. There was some dialogue, and in the fall of 2014, official negotiations were held between the government and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP).

Deputy Prime Minister Yalçın Akdoğan and Interior Minister Efkan Ala negotiated with three parliamentarians from the HDP. They started the talks with a common goal which might seem too ambitious: to develop a long-term plan for a peaceful solution between the PKK and the Turkish state.

HDP negotiators visited Abdullah Öcalan in İmralı prison several times. The two ministers discussed the progress of the negotiations with the prime minister and his closest associates. As per the constitution, the president had no political power at the time. His role in the government was primarily symbolic, and it was the government that had executive power. Erdoğan had resigned as prime minister in August 2014 and was only president during the negotiations, thus, he did not participate in these negotiations.

On February 28, 2015, the government and HDP delegations concluded the first phase of negotiations with a press conference at the Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul. They could hardly have found a building with greater symbolic significance: six sultans lived in the Dolmabahçe Palace from the time it was built in the mid-1800s. It was also the summer residence of Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish state, who lived his last days there in 1938. From 2007, Dolmabahçe Palace became the prime minister’s official residence in Istanbul.

The HDP delegation visited Abdullah Öcalan the day before the press conference. They came away from this meeting with an outline for the next steps of the reconciliation process. MP Sırrı Süreyya Önder, who led the HDP delegation, had many TV cameras pointed at him as he read out the ten points outlining a way forward. The atmosphere was tense when Deputy Prime Minister Yalçın Akdoğan then took the floor:

“We have reached an important phase in the peace process [çözüm sureci – the solution process]. The HDP group was in Imrali yesterday and attended a meeting [with Öcalan].” He could not have come much closer to formally recognizing Abdullah Öcalan as a peace negotiator.

Then Akdoğan moved on to the question on everyone’s minds – whether the government would continue on the path they had begun. The deputy prime minister commented on the ten points the HDP had put forward, saying “we [implied: the government] consider the statement important, in order to speed up the process of dismantling and removing all weapons, so that we have an environment without armed operations. And so that we can use democratic politics as a tool.”

Listening to these historic words was like reliving the time I had heard Öcalan’s Newroz message in Qandil barely two years earlier. He spoke then about ending armed struggle and resolving conflicts through democratic politics.

After first discussing the way forward with the prime minister and those closest to him, the deputy prime minister’s message echoed Öcalan’s.

Leaders from the HDP and the government dominated newspapers and television that day. The images of the negotiators shaking hands with each other announced that something historic had happened. While the conflicts had not been resolved, the government and the Kurdish representatives had announced that the reconciliation process would continue.

Then President Erdoğan said to stop. He was against reconciliation and publicly criticized the government.

One of the deputy prime ministers responded on behalf of the government, writing that Erdoğan’s statements – “I don’t like it”, “I am not happy about it” – were merely emotional expressions of his own views.

“The peace process is carried out by the government and the government is responsible for this issue,” the deputy prime minister stated.

Erdoğan did not budge. He publicly rebuked the government: “I consult my people on every issue. I am the president.” He received a clear response from the deputy prime minister: “Don’t forget that this country has a government.”

When Ahmet Davutoğlu became prime minister in 2014, many thought he would just be a puppet for President Erdoğan. But in his passionate speech on Newroz Day in 2015, he showed that he was not a puppet at all – he stated that the new peace process meant that the time had come to “bury any culture of hatred forever”.

April 2015: Renewed isolation of Öcalan

Less than two weeks after Prime Minister Davutoğlu’s Newroz speech, news broke that President Erdoğan had overpowered the government: on April 5, 2015, Abdullah Öcalan was once again completely isolated in Imrali prison. The most important advocate for peace had once again been confined to the four walls of his prison cell. The president had seized power in violation of the constitution. He had canceled the entire peace process.

June 2015: Erdoğan loses the election.

The election campaign in Turkey in the spring of 2015 was characterized by acts of violence, mainly directed against the HDP. A brutal bomb attack by ISIS interrupted the HDP’s last mass meeting in Amed (Diyarbakır). Party leader Selahattin Demirtaş was on the podium when the bomb went off. I was impressed by the composure he showed.

When Turkey’s voters went to the polls on June 7, 2015, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and President Erdoğan had one goal: to have 330 representatives in Parliament. This majority was needed to change the constitution and introduce presidential rule. The election was to legalize Erdoğan’s abuse of power. He displayed great confidence in the run-up to the election.

June 7, 2015: Disaster strikes for president Erdoğan

The AKP lost almost a fifth of the support it had had during the previous election and gained only 258 seats in parliament. This setback was made even more severe as the HDP broke the 10 percent threshold. Figen Yüksekdağ, Selahattin Demirtaş and their party colleagues won the election. Had Turkey been a democracy, everyone would have accepted the clear message from voters: We do not want a one-party government, and we don’t want presidential rule either.

But President Erdoğan did not accept the voters’ decision. He decided that there would be a new election on November 1 and restarted his election campaign by announcing, on July 24, a new war on terror – both against Daesh (ISIS) in Syria and against the PKK.

Four days later, NATO held a summit in Brussels, where the NATO secretary general Jens Stoltenberg announced that all of NATO stood behind Turkey in this new war: “All allies expressed their strong support for Turkey and we all stand united in solidarity with Turkey.”

After a few near-symbolic sorties against Daesh-controlled areas in Syria, Erdoğan ordered the pilots to concentrate their airstrikes on Kurdish areas in Turkey, Syria and Iraq. The village of Zergele in northern Iraq became one of the first targets of bombing under Erdoğan’s new “war on terror”. Nine civilians were killed in this first attack. Later, I saw the ruins of the six houses that had been destroyed.

Six months after the attack, I met Firsat Sofi Ali (1978 – 2020) in Hewlêr (Erbil). He belonged to Masoud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and was a member of the regional parliament. Ali was from Zergele and visited the village right after the Turkish attack.

“There were only civilians in our village”, he said. “After the attack on Zergele, we have now had eight years of state terror and war. You can like or dislike Abdullah Öcalan. And many more than NATO chief Stoltenberg and President Erdoğan see him as a dangerous enemy. But even they should realize today that there is no path to peace in Turkey without Öcalan’s re-engagement in the negotiations. The release of Öcalan is the first step.”

- Erling Folkvord is a journalist and author, a member of the Norwegian Red Party, a former member of the Norwegian parliament, the leader of Solidarity with Kurdistan and a member of Oslo City Council.