Erling Folkvord

Before allowing heads of state to mark a century since the victors of the First World War concluded a series of peace agreements, we should examine these agreements’ content and implications.

📌 #AUDIOARTICLE | Erling Folkvold sheds light on the Lausanne Treaty's relevance in 2023. Explore the hidden dynamics and geopolitical implications behind this historic agreement. #LausanneTreaty

🖊 Erling Folkvordhttps://t.co/77EyCgJHHD pic.twitter.com/lFjl9J1U3S

— MedyaNews (@1MedyaNews) July 5, 2023

In West Asia, the dominant imperialist powers, England and France, had one main goal following the war. Together with their allies, Italy, Greece and Russia, they aimed to crush the Ottoman Empire. The 600-year-old superpower that had dominated this part of the world was to be removed from the map. Then they were to divide the lands into regions under English and French influence and control. This much was already agreed upon in 1916, when the secret Sykes Picot Agreement laid out this war objective. The agreement was kept secret, until the Bolshevik Party in Russia crushed the Tsarist regime in the October Revolution of 1917. The new revolutionary regime opened the Tsarist archives, and published the Sykes Picot Agreement.

Upon the war’s completion, there were many “peace” conferences. The penultimate one was completed in 1920 in Sèvres, a district in Paris. The subject of negotiations was simple: How should we, the victors of the war, divide Anatolia and the European part of the Ottoman Empire between us? The land in question constitutes most of the land that today makes up the state of Turkey.

Geographically and politically, the Sèvres negotiators created a “patchwork” that proved impossible to implement. The Sèvres Agreement divided multicultural Anatolia with artificial borders.. The victors of the war were to each take their share, as shown on the map.

A delegation from Constantinople (Istanbul) representing the Ottoman Empire and its defeated Sultan was present. Everyone knew that the Sultan’s time was up, and that the signatures from his delegation were not going to have any political significance. A planned Turkish state was entered on the map laid out at Sèvres, constituting a small area without a coastline towards the Mediterranean Sea.

The Sèvres Agreement was essentially an agreement in which European imperialist powers divided up Anatolia based on their own interests, just as they had already divided the remaining Ottoman territories which today make up Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel/Palestine. No-one should suspect them of caring about the interests of the people.

A ray of hope for Armenia and Kurdistan

Nevertheless, the Sèvres Agreement offered some hope for Armenia and Kurdistan. The agreement recognised the new state of Armenia. This happened seven years after the Turkish genocide of the Armenians. A few months later, Soviet military forces moved into Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, and Armenia became a Soviet republic until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Three articles of the Sèvres Agreement (Articles 62, 63 and 64) mention Kurdistan. There are very vague formulations, no clear boundaries and many reservations. The Kurdistan that the agreement describes covers only a small part of the area where the Kurds were and still are the majority of the population. Nothing should happen until “the present treaty enters into force” (Article 64), and the Sèvres agreement never did enter into force.

Article 64 of the agreement nevertheless used the phrase “such an independent Kurdish state”. Since then, many have rightly claimed that England, France and Italy pledged to support the creation of an independent Kurdish state. This was political double-dealing, albeit only one of many such cases. Both after the War and throughout more recent history, great power leaders have used beautiful but non-committal words to give the impression that they support the liberation struggle of oppressed peoples.

The National Pact and General Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa Kemal was a famous and highly skilled general in the Ottoman Empire. In 1919 he deserted from the Ottoman army and started negotiations with Kurdish clan leaders. These meetings discussed the future of the Ottoman Empire and how the polity might defend itself against non-Muslim threats.

After protracted negotiations, the National Pact (Misak-ı Millî) was adopted at the Sêwas Conference in September 1919. It was a platform with a religious basis, intended to defend the Caliphate and the Ottoman regime against infidel conquerors.

Before the decision, Mustafa Kemal gave a fiery speech, asserting: “As long as there are people with honour and respect, Turks and Kurds will continue to live together as brothers around the institution of the Caliphate, and an unshakeable iron tower will be raised against both external and internal enemies.”

At this time there were many local defence organisations. At a conference, it was decided to gather all these in the Association for the Defence of the Rights of Anatolia and Rumelia — Rumelia being the Ottomans’ term for the European part of the Ottoman Empire.

The National Pact called for the preservation of the borders of the Ottoman Empire, with the exception of the Arab territories lost during the First World War. General Mustafa Kemal was elected commander-in-chief of the Muslim forces in the fight against the non-Muslim Armenians, Greeks and several others. At that time there was a broad mobilisation for a defensive war against imperialist powers and their allies.

Neither Turks, Kurds nor other nationalities are mentioned in the National Pact. But the pact determined the borders of the new state, as shown in the map below. The national pact includes, among other things, the northern parts of present-day Syria and Iraq.

For the next few years, as long as the War of Independence lasted, Mustafa Kemal defended this religious platform. Though it may be surprising for many to hear, the founder of the modern Turkish state did indeed promise the Kurds autonomy in the areas where they were in the majority.

The Indian freedom fighter Jawaharlal Nehru (1889 – 1964) was one of many who at the time looked to Mustafa Kemal as a role model for anti-imperialists. After liberation from British colonial rule, Nehru became the first Prime Minister of India.

Mustafa Kemal himself did not utter a word to suggest that his real goal was something completely different from what was agreed on in the National Pact: After victory in the War of Independence, he was to abolish the Muslim caliphate and establish a secular and super-nationalist state that would be for Turks only.

A few years after the state of Turkey was established, Mustafa Kemal took the name Ataturk. It means the father of all Turks. By then, Ataturk’s soldiers had defeated and killed thousands of Kurdish freedom fighters.

Lausanne 1923: The great power interests of England and France

It has now been almost 100 years since the victors of the First World War once again met with some of the vanquished. They met in Lausanne, in neutral Switzerland. By this time then Ataturk had won the War of Independence, and the Sèvres Agreement was politically dead.

England and France’s regional aim in the World War had been to crush the Ottoman Empire and establish French and British colonies. This goal was fixed. But Mustafa Kemal’s victory in the War of Independence put a spoke in the tires. Now the colonial powers had to make the best of the new situation. England and France agreed that the peoples of the region should get nothing, but the two were otherwise in agreement. The World War was an imperialist war. Kurds, Arabs, Turks, Palestinians and many others had defended themselves, and most had lost.

Mustafa Kemal won important political victories in Lausanne. The Great Powers gave up their plans to divide Anatolia into eight parts. He obtained approval for the new state of Turkey, which had not yet been established, to encompass practically all of Anatolia. Neither Kurdistan nor Armenia was mentioned at all.

But England and France said no to the boundaries of the new state as described in the National Pact. The major powers were still imperialists and did not want to give up the oil and gas-rich areas of northern Iraq and northern Syria.

The Turkish delegation that travelled home to Ankara therefore had to report on both victory and defeat. For Kurdistan and the Kurds, who had not even been allowed to participate in the negotiations, it was only a loss.

A peace agreement that ‘put an end to peace’

The English Field Marshal Archibald Wavell served on the Palestinian front during the World War. He later became the Viceroy of India. As early as 1920, he characterised the peace negotiations by saying: “After the ‘war to end war’, they seem to have been pretty successful in Paris at making the ‘Peace to end Peace.’”

The field marshal was right. In the last 100 years, there has not been a single year without war in one or more of the countries that were created after the pulverisation of the Ottoman Empire.

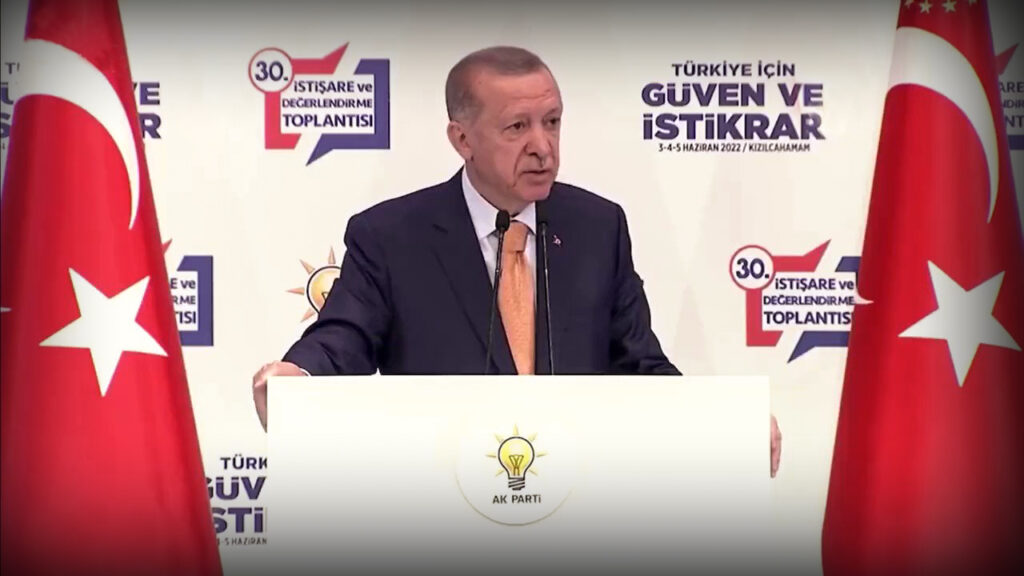

In recent years, Turkey has been waging war in both Syria and Iraq. The wars are ongoing in areas which, according to the National Pact, were supposed to become part of Turkey. At home in Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan repeats again and again that he will accomplish what Ataturk failed to do. He must realise the National Pact – and that means moving state borders. Turkish Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu put it this way when he visited the Turkish occupation forces stationed in Iraq in April 2021: “Our goal here is the same as in Syria. We have come to stay in Iraq.”

Erdoğan will surely try to make 24 July 2023 a campaign day for the wars he and NATO’s second largest army are waging in Syria and Iraq. I, for one, hope he fails, and that Lausanne 2023 will instead be a day of protest and celebration, a step toward a future in which the Kurds and the other peoples in the Middle East achieve freedom and equal human, linguistic, cultural and democratic rights.

It is to be hoped that Lausanne 2023 marks a step toward this this demand. But to begin moving toward this goal, it will be necessary to drive back NATO’s occupation forces currently stationed in Iraq and Syria.

Erling Folkvord is a journalist and author, a member of the Norwegian Red Party, a former member of the Norwegian parliament and a national board member of Solidarity with Kurdistan.