By Mahmoud Patel

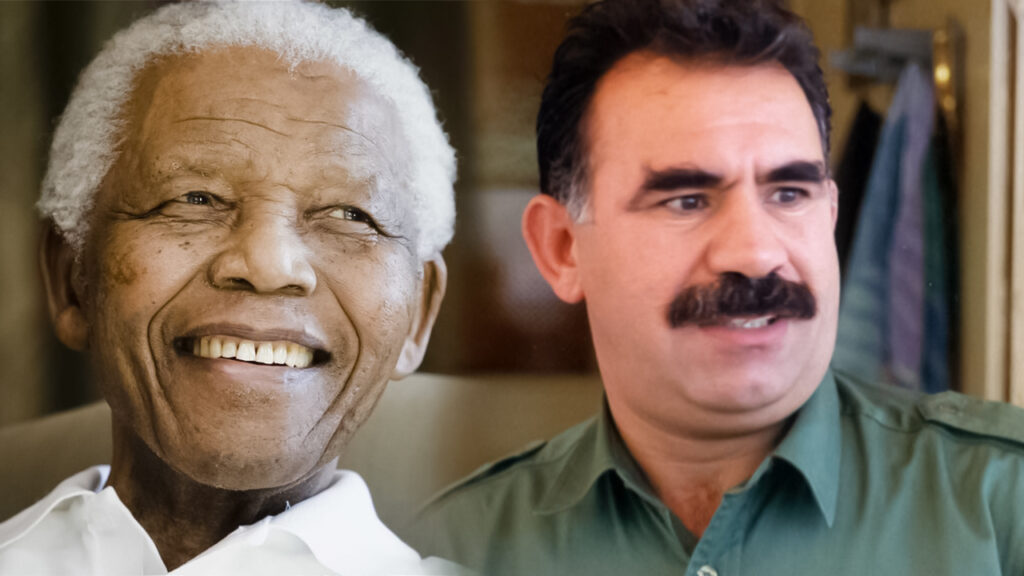

Nelson Mandela and Abdullah Öcalan, two monumental figures from disparate corners of the world, share an unbreakable bond in their relentless pursuit of justice, freedom and human dignity.

Öcalan has been imprisoned in Turkey’s İmralı Island prison for nearly 25 years under severe conditions of isolation. Mandela was held on another island prison, Robben Island, for 18 of his 27 years behind bars in South Africa.

For this entirely fictional dialogue I wrote for Medya News, I was inspired by a similar recent piece which set up an imagined conversation between the Kurdish political leader and Mohandas Gandhi, the iconic father of the modern Indian nation. I wanted to explore the links between Öcalan, often referred to as “Apo”, and Mandela, affectionately known as “Madiba”. These titles acknowledge the significance of their roles in their respective struggles and the impact they have had on their peoples, and on the world.

Shared Trajectories

Nelson Mandela (NM): Greetings, Mr. Öcalan. Your intellectual and strategic prowess, and leadership as “Apo” in the Kurdish struggle, have been a beacon for many.

Abdullah Öcalan (AO): Thank you, Mr. Mandela, or should I say “Madiba”? Your indomitable spirit and tactical brilliance have been a guiding light for oppressed peoples everywhere.

NM: Our paths have been fraught with challenges. What insights have you gleaned from your journey?

AO: Madiba, my experiences have taught me that the struggle for justice is a complex interplay of resistance and diplomacy. It’s not merely about overthrowing oppressive regimes, but about constructing a new social contract that is rooted in the principles of direct democracy, ecological sustainability and women’s liberation. Our struggle, like yours, seeks lasting peace.

Radical Beginnings, Long Roads to Peace

NM: Apo, your philosophy of democratic confederalism has sparked global interest. Could you elaborate?

AO: Democratic confederalism is not just a political system; it’s a social revolution. It dismantles the patriarchal and capitalist structures that have long subjugated our people, replacing them with a decentralised, direct democracy. It’s a model that transcends nationalism, advocating for a pluralistic society where multiple ethnicities, religions and languages coexist in harmony.

NM: How do you envision the role of leadership in this new paradigm?

AO: Leadership in democratic confederalism is not about wielding power; it’s about empowering. Leaders are not rulers but facilitators, who ensure that the mechanisms of direct democracy are accessible to all, especially the marginalised and disenfranchised.

NM: Apo, both our movements had radical beginnings, and our respective struggles for justice involved the adoption of armed struggle at some point. Can you share your perspective on the right to self-defence in the face of oppression?

AO: Madiba, the right to self-defence is a fundamental principle when people are subjected to severe oppression and violence. In our case, the Kurdish people faced systemic discrimination and brutal repression for decades, which led to the need for self-defence. However, we always believed that armed struggle should be a last resort when all peaceful avenues have been exhausted.

NM: I can relate to that sentiment. In South Africa, we initially pursued non-violent resistance, but the harsh response from the apartheid regime pushed us towards armed struggle as a means of self-defence. However, we never abandoned the hope of a peaceful resolution and continued to engage in negotiations.

AO: It is reassuring to hear that you also maintained the pursuit of peaceful solutions. We, too, have sought political dialogue and negotiations whenever possible. Our aim is to resolve conflicts through peaceful means and build a democratic and just society.

NM: Trust-building is a cornerstone of any transition. How have you navigated this delicate process?

AO: Transitioning from armed struggle to peace requires ceasefires, dialogue and ongoing efforts. Geopolitical factors have impacted our struggle, but our commitment to justice remains unwavering. We’ve initiated unilateral ceasefires, engaged in peace talks, and even while incarcerated, I’ve penned numerous treatises advocating for a peaceful resolution and continued advocating for justice. These are not mere gestures but tangible commitments to a peaceful future.

Struggles in Prisons and Minds

NM: Our incarcerations became symbols of resistance. How did you maintain your resolve?

AO: Imprisonment, Madiba, is but a physical constraint. They can confine us behind walls, but they cannot imprison our ideas, our philosophies, or our resolve to fight for a just world. Even from the confines of my cell, I continue to write, to inspire, and to strategise. They didn’t break our spirits.

NM: Apo, what intrigues you about our struggles?

AO: I find the role of education in advancing justice and freedom intriguing. How do you see its importance?

NM: Education empowers individuals and counters prejudice. We promoted education as a tool for justice.

AO: Education empowers our people and challenges oppressive ideologies in our struggle.

NM: We share the belief in education’s power to bring about change. What other common values do you see?

Ubuntu and ‘Jin, Jiyan, Azadi’

AO: Our shared commitment to justice, freedom, and dignity unites us despite different contexts, as represented by our slogan, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi”. Despite our unique journeys, we share a commitment to the principles that “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” represents – a commitment to a just and inclusive society where all individuals, regardless of gender, have the opportunity to live in freedom and dignity.

NM: Apo, I’d like to share with you a concept that holds great significance in South Africa, known as “Ubuntu”. It’s a Nguni Bantu term that can be roughly translated as “I am because we are” or “humanity towards others”. Ubuntu represents the interconnectedness of all people and the idea that our well-being is intrinsically linked to the well-being of others. In essence, it embodies the spirit of compassion, empathy, and community.

AO: Ubuntu is a beautiful and profound concept, Madiba. It resonates with our principles of solidarity and shared responsibility.

NM: Despite our different contexts, our aspirations for a just and compassionate society unite us.

AO: Absolutely, Madiba. The powers that be have often tried to thwart these aspirations, but the resilience of our movements and the righteousness of our causes will ultimately prevail.

NM: Indeed, you were en-route to South Africa and we would have given you political asylum. The involvement of intelligence agencies adds a layer of complexity to our incarceration that lays bare the hypocrisy of the so-called democracies. In my case, it was essential for the apartheid regime to maintain its grip on power, and external support may have played a role in their efforts to suppress our movement. International pressure and advocacy are crucial to improving the conditions of political prisoners. For example, labels like “terrorist” have been applied to both of us, but the world now views our struggle very differently to how it once did.

AO: Labels can overshadow the broader context of our struggle for justice, but diplomacy can lead to change.

NM: Such labels can have profound implications, both politically and in terms of international perception. However, it’s essential to recognize that these designations can change over time, as demonstrated by my own journey from political prisoner to president.

Symbols of Resistance

AO: Madiba, your journey to freedom is an inspiring example of how perceptions can evolve. Our stories show that the pursuit of justice and freedom can come at great personal cost but carries the hopes and dreams of many.

NM: Our imprisonments became symbols of resistance and resilience and drew international attention to our causes. Freedom shall prevail for you, and the Kurdish people!

AO: Mr. Mandela, both our experiences are a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit. Yes, freedom shall prevail!

*Legal scholar, academic and human rights activist Mahmoud Patel is the chairperson of the Kurdish Human Rights Action Group in South Africa.