Meghan Bodette

There may be no single sentence that Turkey’s right-wing autocracy under president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan fears more than ‘a society can never be free without women’s liberation.’ Those nine words sparked an international incident last year when the Turkish foreign ministry attempted to threaten the government of Norway into censoring a painting that included them.

If there is one, we could say that it might be “jin, jiyan, azadi,” — which many know by now is a popular slogan meaning “woman, life, freedom,” in Kurdish. A lawyer who said this in solidarity with women-led protests in Iran faced violent threats from colleagues, was briefly detained, and is still under criminal investigation.

These words and the powerful ideas about women’s freedom that they represent seem difficult to object to. But the government of Turkey sees them as a national security threat—and has made it clear that it will meet the women who stand up for them with armed force.

In July, Women’s Defense Units (YPJ) commander Jiyan Tolhildan, renowned for her leadership in key battles against ISIS, and the effort to organise women in northeast Syria, was assassinated as she left a women’s conference in Qamishlo.

In October, Nagihan Akarsel, a member of the Jineoloji Academy, was murdered in Sulaymaniyah. Turkey’s Ambassador to Iraq all but confessed to the killing in response to a journalist’s question days later.

Not long after that, Turkish Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu said that the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) was a ‘women’s organisation’ with ‘philosophies and sociologies’ on that basis in a speech in which he discussed Turkey’s so-called ‘war on terror.’

From an analyst’s perspective, it is not difficult to understand the threat that Erdoğan’s regime perceives here. Kurdish women have proven that they can successfully resist under the harshest conditions and unite women across ethnic and religious lines in the struggle for women’s freedom. In doing so, they have become a potent threat to autocrats and fundamentalists in the region.

In Iraq and Syria, the women of the YPJ and YJA-STAR fought ISIS when better-armed states could not or would not do so. In the territories that they liberated, they spread their ideas about women’s liberation and trained women to defend themselves, seeking to target the patriarchal ideas that enabled ISIS’ rise and ensure that the crimes the jihadist group committed would not be repeated.

Their model caught on quickly. When I visited North and East Syria, some of the most enthusiastic supporters of the women’s revolution I met were Arab women who had lived under ISIS occupation. In a meeting with the Zenobia Women’s Coordination in Raqqa, activists insisted to me that their struggle was relevant not only for one community or one country, but for oppressed women everywhere.

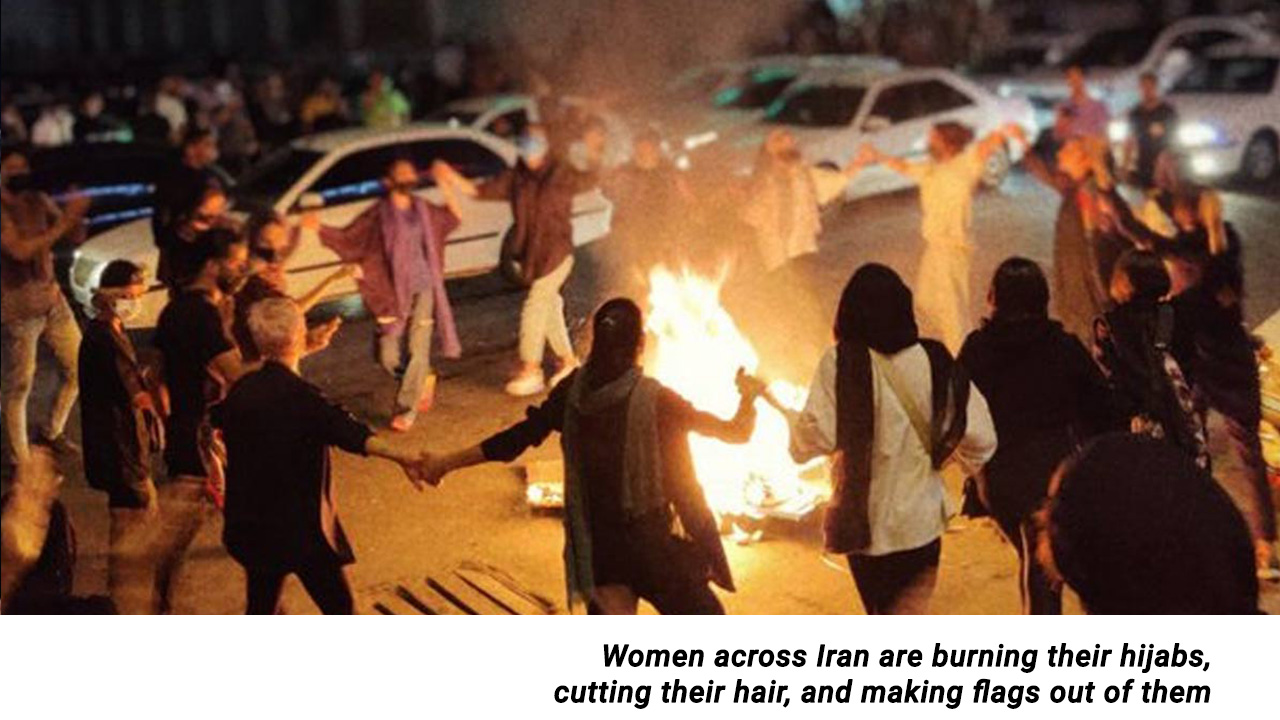

In Iran, Kurdish women’s struggle is at the centre of a nation-wide, multi-ethnic uprising that has shaken the Islamic Republic to its core. Men and women of all backgrounds are chanting “jin, jiyan, azadi” and demanding an end to dictatorship.

The Iranian regime has resorted to massacres, arbitrary detentions, torture and death sentences to crush this women-led revolution, but the people in the streets show no sign of backing down. “Kurdish and Iranian people are now angrier than ever. We are also very hopeful for the fall of the regime and a better future. I want the world to stand beside us and support our movement because it’s for the freedom of women,” a young Kurdish woman I interviewed last month told me.

Erdoğan likely fears that he will be next. The 2023 elections will be existential for his government, and polls show that Kurdish voters may well determine the outcome.

Turkey has already de facto suspended local democracy in Kurdish regions and is attempting to close down the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), leaving its more than five million supporters out of the political process altogether. The campaign to crush Kurdish political aspirations and drum up nationalist support is not confined within Turkey’s borders. Many in North and East Syria fear they will face a third Turkish invasion before the 2023 vote is held.

The impact of these repressive strategies on democracy and human rights in the region cannot be overstated. However, it is important to point out that they have still not achieved their political goals.

Attacks on Syrian Kurds have eroded international support for Turkey’s perceived security concerns, brought on sanctions and arms embargoes, and spurred global sympathy for the Kurdish cause and the revolutionary ideas that North and East Syria is attempting to put into practice.

The ideas of the Kurdish women’s movement in particular are stronger internationally than ever before. I had a powerful opportunity to see this first-hand last weekend, when I moderated a panel at the Second International Women’s Conference organised by the Women Weaving the Future Network in Berlin.

More than 700 women from over 40 countries joined the conference to discuss how women are standing up to the challenges of our time: war, authoritarianism, poverty and exploitation, the destruction of the environment, and more. On the one panel I moderated, leaders in women’s struggles from as far away as Guatemala and Afghanistan presented on their experiences.

While participants made their own critiques and highlighted their own practical knowledge and insights, they all expressed interest in understanding and engaging with the ideological and practical advancements that Kurdish women have made.

Watching over the energetic debates, music and dancing, and multi-lingual feminist protest chants were posters of Jiyan Tolhildan and Nagihan Akarsel. Their faces were a sobering reminder that there are powerful men willing to murder women who dare to stand up for the ideas that we were able to openly debate. Tolhildan was killed just hours after she gave a speech like many of those that we heard, as she left a conference much like ours. Akarsel was an organiser of the Berlin conference.

At the same time, the gathering was a glimpse of what a world with more women like them and fewer men like Erdoğan would look like. Ultimately, a regime that reacts to women’s ideas about freedom with threats and violence does nothing but reveal its own weakness. An idea that attracts worldwide solidarity and support despite a very real danger to the lives of people who engage with it, by contrast, reveals its relevance and power. The Kurdish women’s struggle has outlasted and defeated autocrats and fundamentalists before—and will do so again. I wouldn’t bet against it.

Meghan Bodette is the Director of Research at the Kurdish Peace Institute. She received a Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service from Georgetown University. Her work has been featured by various outlets including the Wilson Center’s Middle East Program.