Sarah Glynn

As I start to write on Wednesday, 14 February, I am imagining Abdullah Öcalan at this time 25 years ago. Since the beginning of the month, he has been in a house belonging to the Greek embassy in Nairobi, which is not where he had intended to be. He knows the world has become an inhospitable place, but he doesn’t know that this is his last day of relative freedom. He has been on the move since 9 October, when he was forced to leave the relatively safe haven of Syria by Turkish threats to invade if Syria continued to host him – threats backed by the United States, the European Union, and Israel.

Öcalan’s presence in Syria had been made possible by cold war politics that had placed Syria and Turkey on opposite sides. After leaving, Öcalan had planned to take his ideas for a peaceful resolution to the Kurdish Question around Europe, but European leaders were not interested in talking about peace with a leftist freedom fighter. They were more concerned not to upset their strategically placed NATO ally and trading partner, Turkey.

Before coming to Kenya, Öcalan’s odyssey had taken him to many different places, including Moscow, Rome, and Athens. At times, prospects had seemed to brighten, and history might have been very different. He got the support of the Russian Parliament, and his asylum claim was accepted by Italy though never made official. But higher authorities and international pressure always intervened. He had been brought to Kenya by the Greek secret service with the expectation that he would be moved on to another country that would give him asylum, such as Nelson Mandela’s South Africa; but the CIA and other would-be captors were circling. Within the embassy space, Öcalan was relatively safe, but he couldn’t stay there, and on 15 February, he was told he was being taken to a plane that would fly him to the Netherlands. The Kenyan government insisted that he be taken in a government car, not a diplomatically-protected embassy one, and, on the way to the airport, the car in which he was travelling separated from that carrying the rest of his party, and drove him to waiting Turkish agents. They flew him, bound and blindfolded, to Turkey.

The role played by international governments in supporting Turkey and crushing all radical left dissent has not changed since Öcalan’s abduction, though the drive to please Turkey has become even greater and, since 9/11, “war on terrorism” rhetoric has come into play.

Since his abduction, a quarter of a century ago, Öcalan has been shut away in İmralı Island Prison in the Sea of Marmara. At first, he was sentenced to death, in a trial condemned as unfair by the European Court of Human Rights. When Turkey ended the death penalty, in an effort to comply with the criteria for European Union membership, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. This is life without the possibility of parole, a sentence that has been deemed a form of torture by the European Court because it denies the right to hope.

Imprisonment has also brought years of hardly bearable isolation. Although there are now three other prisoners on the island, interaction is very limited and controlled. Visits from layers and family were always restricted and have now been refused completely. Next month it will be three years since the İmralı prisoners have been allowed any contact at all with the world outside their prison, bar a visit, in September 2022, from the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture, who’s findings are confidential.

Prison allowed Öcalan time to develop ideas that had been growing within the movement. His prison writings, ostensibly his defence against his imprisonment, have produced a galvanising political theory that has inspired people well beyond the Kurdish movement, and has informed the establishment of the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, when so many left movements lost their way, the Kurdish Freedom Movement, under Öcalan’s guidance, forged a new path. Drawing on ideas from other political theorists, such as Murray Bookchin, he inspired a system that values ethics and mutual support and that is famous for its focus on women’s rights and the peaceful coexistence of different communities.

Never forgotten

If the international plotters thought that removing Öcalan would finish the movement he led, they were in for a disappointment. The Kurds’ immediate anger shocked the world, with protests lasting for weeks. Many people went on hunger strike, and some – against the express wishes of Öcalan and the PKK – set themselves alight. The Kurdish Freedom Movement identifies itself closely with their imprisoned leader, seeing the oppression and marginalisation of Kurds in Turkey as an extension of his torture of isolation. But his removal has not stopped them from organising: far from it. And it has not stopped the mobilisation of a new generation of activists who were not even born at the time of Öcalan’s capture.

Campaigns for Öcalan make their arguments at different levels. The most basic demand is at a personal level: that Turkey treats him according to fundamental human rights standards, as defined by international and Turkish law. These stipulate that he be allowed regular access to his family and his lawyers, and also communication through telephone and letters; that the use of isolation is kept to a minimum; and that he be allowed the right to hope for parole.

Other demands focus on enabling him to play his key role in any possible future peace agreement that could allow Kurds in Turkey to live in dignity. Comparisons are made with the role played by Mandela, and it is pointed out that such a peace is also vital in order for Turkey to achieve a more democratic future and for peace in the wider region.

On top of this, it is a loss to humanity to lock away a philosopher and prevent them from communicating. Öcalan’s prison writings were written under difficult circumstances and without much possibility of discussing their ideas with other thinkers. Now he is even more restricted, with no way to engage with the wider world. He should be free to contribute to human understanding.

This 25th anniversary is a time for even stronger calls and actions for Öcalan’s freedom. His importance is clear from the many events and from the involvement of people from all parts of the world, including the mainly young internationalists who marched from Basel to Strasbourg. Strasbourg is the home of the Council of Europe, which is supposed to be the guardian of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law, and other marches also converged on the city. Kurdish youth marched from Mannheim, and a 25-day march brought 25 people from Paris. A separate three-day march took place in the south of France and there have been many demonstrations, short marches, and street stalls. The main European rally takes place today in Cologne, and buses have been arranged to bring people from across Europe.

In Turkey, a Great Freedom March departed from Van and Kars on 1 February, and the two parts converged in Diyarbakir for the final stretch to Öcalan’s birthplace in Amara village, in Urfa. While the European marches tried to inform people about Öcalan in the places they stopped at, the Great Freedom March passed though Kurdistan and was welcomed with noisy rallies.

In the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, including the Aleppo neighbourhoods of Ashrafieh and Sheikh Maqsoud, all shops closed on Thursday, and people came out in huge marches in the main cities.

Conferences have taken place in Bilbao (on the situation of Öcalan and solidarity work in the Basque Country), in Rome (on jineology, Öcalan’s feminist theory), in Uppsala (on Kurds in Turkey), in Antwerp (on freedom for Öcalan), in Şengal (a workshop for Yazidi and Arab women), in London, and in the EU Parliament in Brussels (on Turkish political prisoners).

For thousands of political prisoners in Turkey’s jails, their contribution to the Freedom for Öcalan campaign is a hunger strike that is now on its 83rd day. This is currently a rolling hunger strike, with groups of around five people forgoing food for ten days at a time and then being replaced by a new group, but the prisoners threaten to “take it to the next level” if Öcalan’s isolation continues beyond the local elections at the end of March.

Electoral politics in Turkey

Öcalan and the PKK made the decision to take up arms because Turkey allowed no opportunity to struggle for Kurdish rights through political means. As the DEM Party – the current iteration of leftist pro-Kurdish party – can testify, possibilities are still severely restricted, and simple political involvement can still land you in prison. For the 108 defendants in the ongoing Kobanê case, this could be prison for life, without parole.

Mass detentions are expected to increase in the run up to the local elections. On Wednesday, Turkey’s Interior Minister claimed that 179 people had been detained in 22 provinces. Also Wednesday, 11 DEM Party youth members were violently detained in house raids for taking part in the Great Freedom March.

The DEM Party have put together a summary of illegal voter registration in 21 constituencies where they would have been expected to do well in the upcoming local elections. These blatant frauds are of a sufficient scale to tip the balance against the party, and there may be more frauds that are not so easily detected. Here, as an example, I give their findings from Siirt City Centre, which the HDP (the DEM Party’s predecessor) won in 2019 with 33,227 votes, compared to 31,611 votes for the ruling AKP. Since the general election in May, voters registered at one address increased from 10 to 3,009, and at another address, which belongs to the police, the number of voters increased from 7 to 1,996. At a third address, which didn’t previously exist, 2,555 men have been registered who haven’t previously voted in Siirt. And 1,533 voters who previously voted overseas are now registered at addresses in the city.

The DEM Party, like the HDP before it, follows Öcalan’s ideas, and many members and politicians were involved with the Great Freedom March.

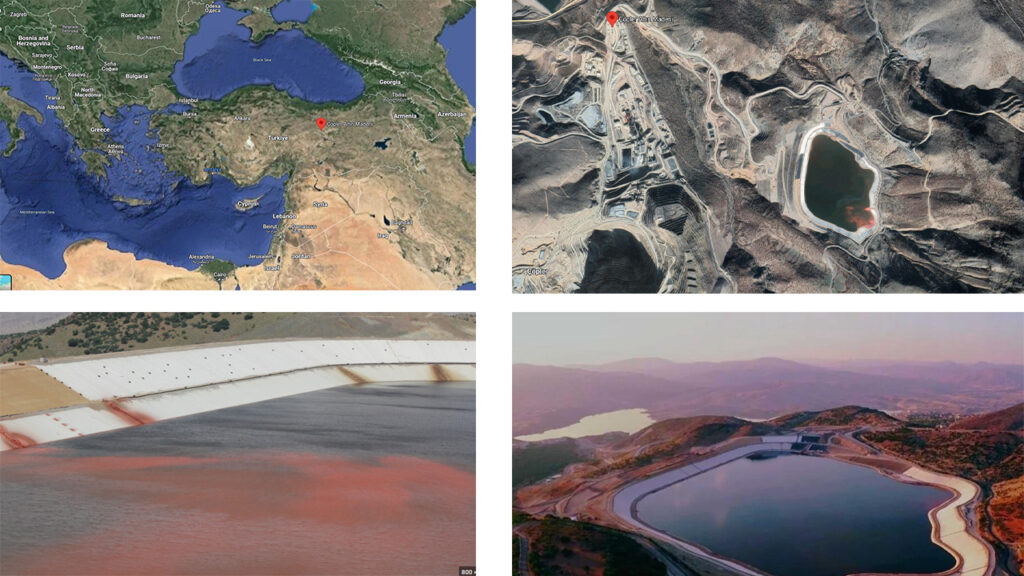

Environmental disaster

Greed, deregulation, and negligence turn Turkish industries into disasters that are waiting to happen. In the case of the open pit gold mine in Erzincan province, which witnessed a devastating landslide on Tuesday, disaster had even been predicted in a television documentary as well as warned about by the miners who worked there. Nine miners are trapped under the collapsed material, and there are fears that large areas of land could become poisoned by cyanide and by other chemicals that were used to extract the gold from the ore. Poison could also get into the nearby Euphrates. This is a mine that has caused problems with leaking cyanide in the past. An environmental activist who posted about his fears of large-scale disaster has been arrested.

In North and East Syria

Ecology is one of Öcalan’s guiding principles, but in North and East Syria, the pressures of a war economy prevent this from being prioritised. Turkey destroys the regions ecology, too, both deliberately and as a by-product of their other attacks. Now there are fears that oil fields bombed in Turkey’s recent attacks are polluting the rivers.

On Sunday, Turkey targeted a centre for rehabilitating the war wounded in Qamishli, killing two YPJ commanders and injuring many others. There are very few resources for the many people who lost limbs or were otherwise damaged in the fight against ISIS, and this was one of the places that was helping them.

The situation is still unstable in Deir ez-Zor where the Syrian Democratic Forces report coming under attack both from militias backed by the Syrian Government and from militias backed by Iran.

In the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

In Sulaymaniyah, in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, security forces prevented a demonstration for Öcalan, and over 20 people were detained. This is the main city that is controlled by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which Turkey likes to accuse of being close to the PKK.

In the other half of the region, dominated by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), there has now been no contact with Roj News journalist Suleyman Ahmed for 113 days, since he was detained by security forces when returning from visiting his family in Aleppo after his father had died.

In Iran

News from inside Iran has dropped off the headlines, but, in another reminder of the intolerance of the Iranian regime, Jina Amini’s family continue to be targeted. Her uncle has just been sent to prison for five years. The family have no intention of keeping quiet, though, and have made their determination clear. As Jina’s brother, Askan, previously explained, “Even the glass of your tombstone bothers them. Break it a thousand times, we will fix it again, let’s see who gets tired.”

That phrase seems to sum up the essence of Kurdish resistance.

*Sarah Glynn is a writer and activist – check her website and follow her on Twitter