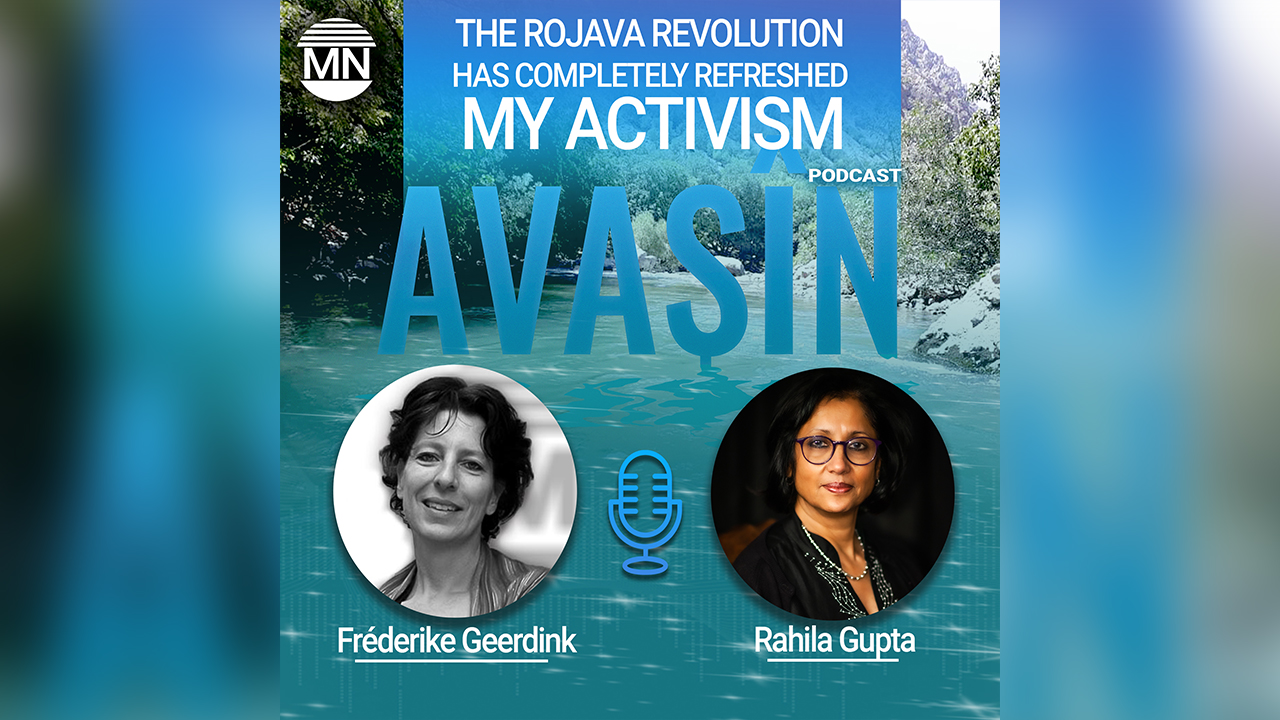

by Fréderike Geerdink

The revolution in Rojava, or North and Northeastern Syria, has “completely refreshed my activism”, said writer and feminist Rahila Gupta in a new episode of Avaşîn podcast. After having waged a struggle against racism and sexism, mainly focused on trying to eradicate gender-based violence against women, in London for forty years, visiting Rojava gave her new insights. “The level of commitment of going from home to home to talk to people about their vision for a new society… I am not sure if we have that kind of commitment in the west. It’s what makes a difference.”

Not that her activism didn’t make a difference, let there be no misunderstanding. Author Rahila Gupta has been part of the Southall Black Sisters, a feminist group in the Southall district in London with a largely Asian-British and Black community, since the 1980s. The source of her struggle, she said, was her upbringing in a communist family, although she only started to be politicized when she was a student in London, UK. Gupta: “I was born in the UK but grew up in India from the age of five months until I returned to London to study. Experiences with racism politicized me. I got in touch with Black feminism, with groups in which the struggle agaisnt racism and sexism were connected.”

Police on horseback

The Southall Black Sisters had been founded in 1979, when a gathering of the fascist white British group in a community centre in Southall triggered a huge demonstration by locals. The demonstrators considered the meeting a provocation, but the local council gave permission for it anyway, after which the police did not protect the locals against the fascist group but attacked the protestors. Gupta: “Police on horseback were charging against the mainly young men who were protesting, one of the protestors died. Many young men were prosecuted for breaking the peace and such, and the community stood with them during the trials.”

But the women in the community couldn’t help but notice that there was a fair amount of sexism from the male comrades, including harrassment, and that the men were not comfortable with campaigns against that sexism. Gupta: “A woman and her four daughters were burned in their homes by the husband. Women wanted to campaign against that, but men tried to downplay it by saying the man was just an alcoholic, an isolated incident, and that building a campaign around it would expose the underbelly of the community to the ‘host society’. They considered women who wanted to campaign against such violence ‘home breakers’.”

Virginity

She shivers when she thinks back of another reality of those days: “I shiver because this actually happened in the UK in my lifetime: to push back against immigration, the government introduced a policy to check the virginity of women when they came to the UK to marry. They said that if she was not a virgin, she wasn’t coming for marriage but for immigration and could be refused nto the country. So what they actually did was to use the patriarchal values of Asian communities to clamp down on immigration. This was one of the first campaigns in which Southall Black Sisters participated.”

The forty year struggle against gender-based violence but also against racist immigration policies and in favour of women building independent lives, has brought the Southall Black Sisters from street protests to the corridors of parliament and to court rooms, where they demonstrated, lobbied to change laws and defended women. “One of our actions”, she said, asked about their methods of struggle, “was to gather at the house of a family where a woman had died in the name of honour. For example, a woman had committed suicide, but she had been driven to suicide by her husband and his family. We would gather at the house and shame the family in the eyes of the local community.”

“We still do such demonstrations”, said Gupta, “but not enough anymore. Now we take cases to court: for example we managed to free a woman from jail who had killed her husband after years of facing violence from him. And we are invited at the table when there are talks about new legislation. But we retained our radical edge. I mean, when we are not listened to and we can’t reach our objective at the negotiating table, our negotiator will join the street protest again.”

Emergency situations

The work also becomes very personal, in the sense that one of the most important methods the Southall Black Sisters use is to provide individual help for women in emergency situations. They help women escape violent relations, they help them find housing and an income, they organise places for women to meet and strengthen themselves and their communities. In all these decades, they must have saved hundreds, if not thousands of lives.

“Still, it’s been a bit demoralising,” Rahila Gupta said, “that our initial hope was to be revolutionary and radical, that we’d overturn the patriarchy, but even though our ideological framing remains radical, in practice we have to recognise we are reformist. We didn’t overturn anything.”

And that’s where the Rojava revolution comes in. She became aware of it when at a conference about rethinking democracy, she heard Mehmet Aksoy speaking. He was a journalist, film maker and activist and, Gupta said, ‘just a brillant human being’. He was martyred in Rojava in September 2017. Gupta was in the initial stages of a book about the patriarchy, and after she heard Aksoy speak about the Rojava revolution, she decided she had to go see it: “We needed to see this experiment where partriarchy was on its knees, perhaps.”

Forty years

“Initially, I couldn’t quite believe it”, she said. “Such an experiment in the Middle-East, where women are in such difficult positions. I was curious to find out what were the circumstances that had lead to a revolution like that so quickly. But when we were there, it turned out there was a history of forty years of struggle.” She remembered exclaiming: “But we as the Southall Black Sisters have been struggling for forty years as well and we are nowhere near this revolutionary situation!”

The power vaccuum in Syria was important in triggering the revolution, she concluded, but also the ‘immense nature of the political mobilisation’, as she called it: “Comrades went from door to door and spend the whole night or even days if necessary to explain their vision, to explain the history of Kurdistan, the 5000 year history of the patriarchy. This level of commitment! My discovery of the Kurdish women’s revolution has completely refreshed my activism.”

Rahila Gupta considers it a privilege to have seen the revolution with her own eyes, to have seen what is possible. “I think it’s big and it makes a difference. I know the situation is difficult now with different powers trying to take over the land, but I hope the Rojava revolution grows and continues to expand. It brings real hope.”