Kariane Westrheim

Turkey and Syria were hit by a deadly earthquake on 6 February 2023, with its epicentre in the Kurdish-Alevi region of Maras. International media reported daily on the catastrophe, but the story of what happened in the wake of the earthquake has been presented completely differently depending on whether it is Turkish or Kurdish media doing the reporting. The fact that the earthquake has affected Kurdish areas more than any others seems to be forgotten or deliberately omitted.

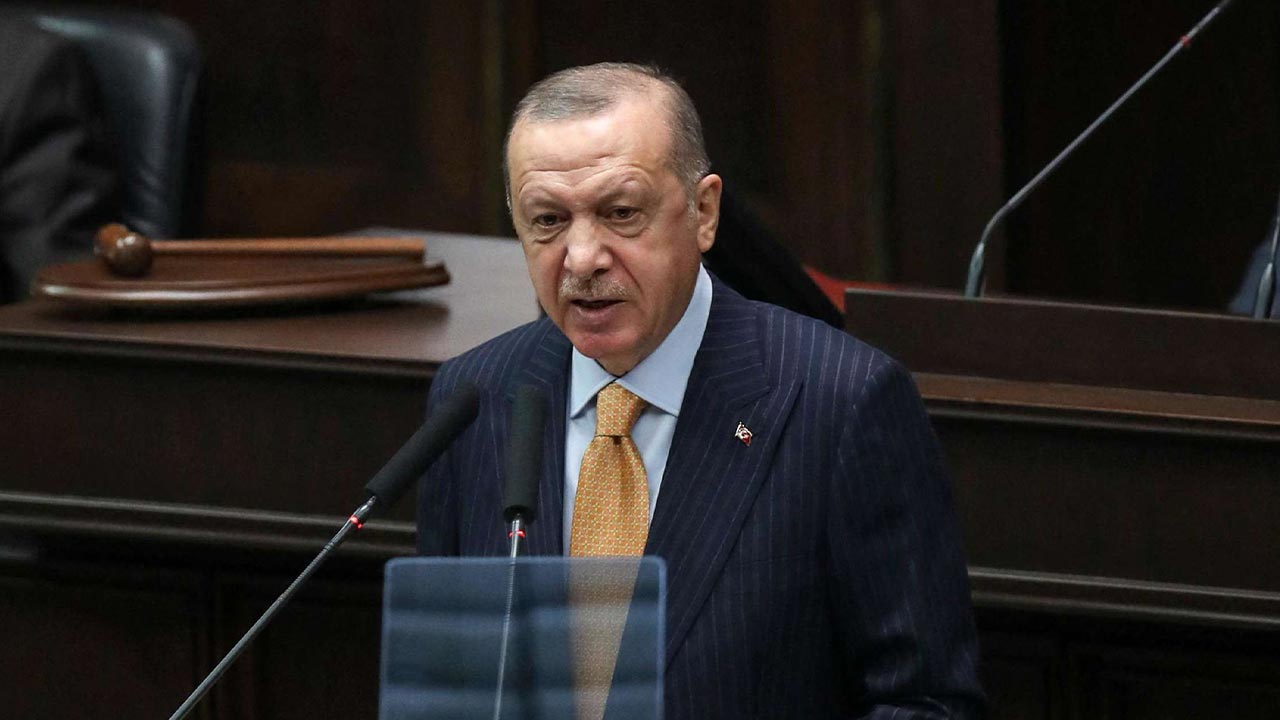

In fact, relief efforts following the catastrophe have been as great a disaster as the earthquake itself – a scandal also largely omitted in the news. Some reports have mentioned the fact that tax revenues supposed to be used for disaster assistance as well as securing buildings against such incidents has instead been used for other purposes. It is no secret that Erdoğan and his government are the ones profiting from the disaster. The state and the contractors who built the houses and tower-blocks that have become the graveyards for thousands of innocent people made a lot of money from these tax revenues ever since a 1999 earthquake.

These financial resources should be used to help people, but instead they have brought death and sorrow to those affected, particularly the people of Kurdistan. As many aid organizations have noted, the first 24 hours after a disaster are vital if one is to save lives. But survivors report that it in fact took several days for rescue teams to begin their operations, and in the meantime, people had to dig with the tools they had to hand.

More than 47,000 people have been confirmed dead in Turkey, Northern Kurdistan, and Syria – with 40,000 of the dead in Turkey alone. Around 85,000 buildings have collapsed or have been badly damaged because of the two earthquakes. Warnings from experts have been ignored for years, so when the catastrophe hit the state was not prepared. Erdoğan was clearly most concerned with saving his reputation, by defining the earthquake as happening due to ‘fate’. Everything points to the state’s responsibility. The AKP-MHP government carries the responsibility for the tragic consequences that followed.

When the State Disaster Management Agency (AFAD) came to the rescue, people reported that the rescue teams came far too late and did not provide any help until long after the earthquake took place. In fact, those who tried to come to the rescue were volunteers and international aid organizations. But fearing what they might reveal if they were allowed into the disaster zone, the state did its utmost to prevent them from reaching the disaster areas.

A state of emergency has been declared and applies until the election in May this year has come and gone. This gives the state, and Erdoğan, the green light to repress what they define as civil resistance – first and foremost from the Kurds, but also the media, and anyone else who raises a critical voice against the regime and its collaborators.

An earthquake is not just a physical event, but most often results in mass death among the civil population. It destroys buildings, infrastructure, irreplaceable cultural monuments and heritage as well as architectural masterpieces. If the destruction of a large scope over the years can be partially restored if not replaced, it is far more difficult to heal the inner mental tremors. People are left with major injuries – physically and not least mentally.

According to the acknowledged Norwegian crisis psychologist Atle Dyregrov, survivors of earthquakes live every day and night in fear of another earthquake, with the grief of those they have lost and with the terrible memories of what they have experienced. The counterbalance to pain, grief and trauma is the contribution of those who want to help, but when reality returns and daily life resumes, people must manage on their own.

Dyregrov also indicates that although the long-term impacts are significant, disasters can also strengthen social ties, promote unity, solidarity and show us the best of humanity. There are many positive examples of how people come together in such crises, support each other, and open their homes for the grieving and homeless. The Kurdish-led People’s Democratic Party (HDP), for example, opened a social emergency centre where thousands already have sought refuge and help.

Children are particularly vulnerable during such disasters. After the earthquake in Turkey in 1999, psychologists recognized that many children needed help to deal with their losses and trauma. They were intensely scared, and everything they encountered that they associated with the earthquakes could trigger strong reactions. They tried to avoid situations and thoughts that reminded them of what was happening, and many had strong bodily reactions.

In several studies, Dyregrov emphasizes, it has been shown that natural disasters dramatically increase psychological problems such as anxiety, tension, irritation and sleep disorders. This contributes to significant mental health problems that make people unable to function in everyday life. With the enormous human losses that the people of Turkey and Syria have experienced, there is little reason to believe that these problems will decrease over time.

Disasters also provoke sensations of ‘loss of place’. These are not only due to the loss of homes and possessions, but also everything those places symbolize, including family memories, inter-generational continuity, and personal investment. We like to think that people have great strength, that they are resistant and relatively quickly can leave such incidents and look ahead, that they can build a new normal after the dead are buried. But what do we know about the duration and extent of the fall-out from disasters like the present earthquake? Just that it will last for years.

It is a reality, though, that the Kurds and other peoples in Kurdistan have experienced oppression, persecution, murder, and ethnic cleansing throughout their history. The present day is no exception. Throughout history, the Kurds have learned to live under such historical conditions and thus to show a unique ability to survive and, not least, to fight back.

The Kurds have literally been knocked to the ground by the earthquake, and by the extreme neglect on the part of the state. It will take a long time to rebuild – not only reconstructing buildings, but healing lives and minds. But the Kurds and other affected people will manage to survive. Kurdish-led led political organisations have called for a show of unity, solidarity and mutual support at this time, to slowly get the people back on their feet. Hope and resistance have carried the Kurds throughout history. Hope is the power that has always helped them to overcome the horrors they have experienced, and it will do so again in the present crisis.

Kariane Westrheim is Professor of Educational Science at the University of Bergen, Norway. Since 2004, Westrheim has chaired the EU Turkey Civic Commission (EUTCC) which among others organise the Annual International Conference on EU Turkey and the Kurds in the European Parliament, Brussels.