In an article for Newayajin, journalist Alin Ozinian focuses on the conditions surrounding Armenian women during and after the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire, through her great grandmother’s story. She emphasises that genocide is not just a one-off event, especially for women and girls; it continues for years and throughout their whole lives.

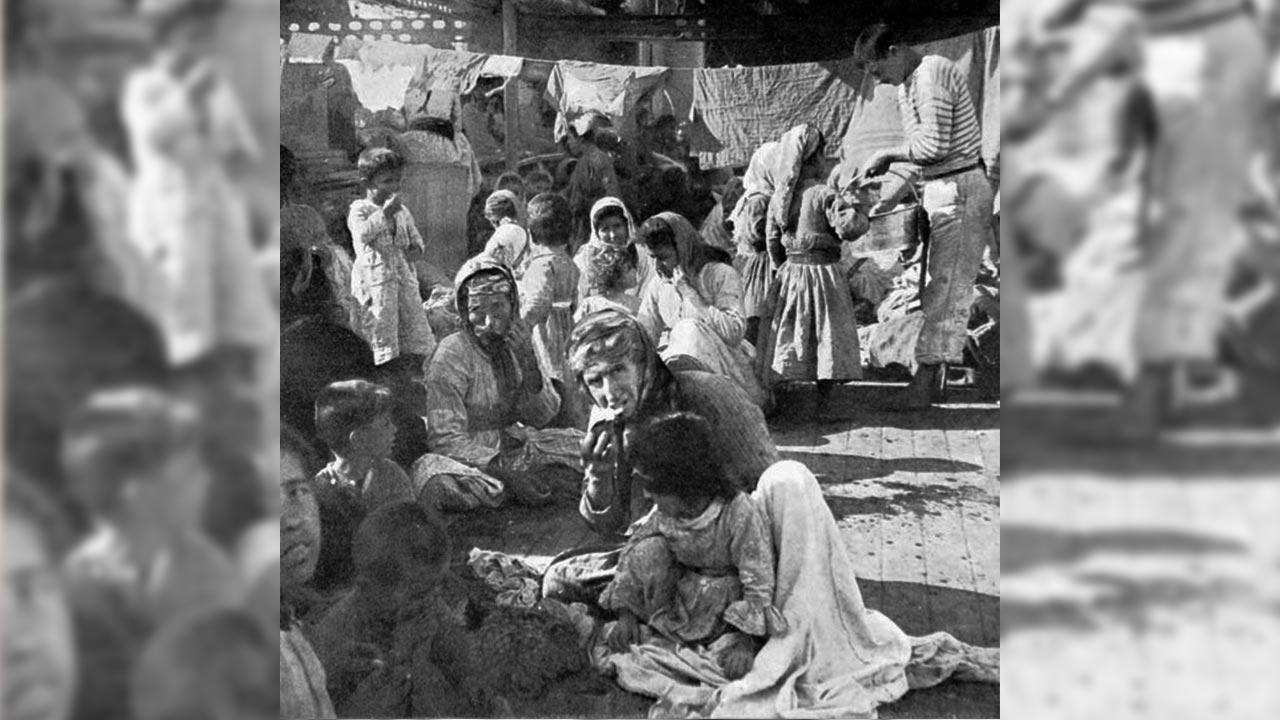

During the Armenian genocide, countless Armenian women and children were abducted, raped, and tortured by soldiers, gangs, and local people. The policy of genocide in play at the time also dealt a blow to Armenian identity. The ‘lucky ones’ among the Armenian women were left on their own after their families were murdered, to be forcibly converted to Islam. They were also made to abandon their mother tongue, their religion, and even their names. The price of their survival was that they had to renounce themselves and their very souls.

Ozinian states that there are very few studies that address the issue of rape during and after the Armenian genocide although it was routine, and that the narratives of sexual violence are softened in oral history studies.

She says that when she was a little girl, she came to face these facts through the story of her great grandmother Martha.

Here is Martha’s story, as told by Ozinian.

Martha lost everything during the deportation. She had very clearly rejected her ‘god’, whom she would entreat for mercy and patience in the life struggle even before she was able to experience the pain of the loss of her brothers, who do not even have graves.

The first ‘strangeness ‘ I became aware of in her was her obstinacy about the church. Once when she saw us going to church on Sunday, she shouted, “Where was God when my brothers’ throats were cut…?” and the other women in the house forcibly covered her mouth so that I would not hear the rest.

There was something about Martha. Everyone wanted Martha to be quiet, whereas I wanted to hear what she had to say. But I was not yet old enough to get her to talk…

Then when I was 12 years old; there was no one at home; I went to her and said: “You don’t believe in God; why? How did God anger you so much?”

She stopped and thought. She was deciding whether or not to talk about it. She chose to talk about it, her eyes staring at a single point, “They say blood was spilled,” she said. “A lot of blood was spilled…”

On that day, I learned from Martha not only the heart-breaking story of one of tens of thousands of Armenian women, but also the story of my family and my ‘unofficial’ history, which was not taught to me in Turkey.

She lived in her house in Ünye, Ordu, with her eight siblings, her mother, whose beauty she talked about all her life, and her father, whose strength she emphasised at every opportunity. One night, in the middle of the night, there was a knock at the door, they were taken outside, and all the villagers were gathered in the square. Children, men, and women were separated. It was the last time she saw her mother, whom she thought was so beautiful, and her father, whom she believed to be strong.

Her eyes opened wide when she spoke about the man who rubbed his thumbs down the children’s throats, not just the first time she told it but every time she told this story. It was as if I saw everything through her eyes, Martha’s child eyes, in those moments. My eighty-year-old grandmother would have been a little girl at the time.

Martha, the youngest child of the family, now also lost her older brothers and sisters, when she was separated off to the place where the small children were. Two men argued about Martha; one said, “No, this one is older. Take her to the back.” “No,” said the other, “She won’t remember anything, let her stay…”

While they were arguing, she ran away, and got lost. She went hungry until someone in uniform, a soldier, found her and took her home.

My grandmother said, “My new ‘mother’ never loved me.” She told me that the soldier tried to convince his wife:

“‘She’ll grow up, she’ll be a help to you, why don’t you want her?’ But his wife used to beat me. When my new ‘father’ came in in the evenings, he would take me in his arms and ask, ‘Did you eat your dinner?’

“In the morning, the wife would beat me again, saying, ‘If you sit on his lap again, I’ll break your kneecaps.’ When I was 13, the wife said to me, ‘you will run away from this house.’ I ran away, and I came here….”

It is not hard to understand why at the age of 13, she was advised by the ‘mistress of the house’ to run away from home. This girl, who would gradually step into womanhood, was now a risk; maybe she would become the second wife. It was not the solidarity of women but the jealousy of women that shaped Martha’s life at that time.

Martha was 18 years old when she came to Istanbul. I never did find out where she lived, how she lived, what she ate and drank, who she dealt with, or what she had been through in the years in between. Whenever I asked her, she cried; she never told me.

I can understand that those years were not very bright for her, as she had to marry a poor man with three children despite being a beautiful and talented woman.

My great grandfather Ardaşes, Martha’s elderly husband, is from Sivas. He was a boy who had managed to survive in that period. He grew up a little and fell in love with the daughter of a Kurdish tribal chief, but the chief would not give his Kurdish daughter to an Armenian, and he could not find any solution other than to flee to Istanbul with his beloved.

But tradition won out. Some years later, they found the lovers, and they killed the girl. My great grandfather was devastated, and his children were motherless. Martha came to their house…

“I raised them, but they didn’t love me; Ardaşes couldn’t love me either, I knew he hadn’t forgotten the love of his life. He used to talk about his wife longingly in the night, and he would cry; I would cry too. I used to cry for myself, for my husband, and for my husband’s wife.”

Nobody wanted Martha to tell me these stories. In fact they forbade her. They would say, “It’s over and done with, don’t mess with the child’s head.” But whenever there was no-one around, and I could find the time, I would be at Martha’s feet. I would ask her to tell me. It seemed to me that she was getting lighter with the telling.

My grandmother is Ardaşes’s youngest daughter and Martha’s eldest. She is the only daughter of two orphan fugitives, of two surviving Armenian children. My 83-year-old grandmother is beautiful, like Martha’s mother, but the stepdaughter of the family, according to her siblings.

Every 24 April, the story, pain, wounds, and struggles of survival of the women of the family I was born into have been ignored. Denial [denial of the Armenian genocide and of the tragedy of the Armenians] deepens in Turkey every April; they call the history of my people an imperialist lie, a lobbying game, treason against the century-old demand for coexistence and equality. The denial overflows from televisions, newspapers, and films.

Countless people are lying in unison. Sometimes I cannot cope with those moments; I close my ears and eyes and think of Martha aged 7, trying to escape from her village, running alone, 107 Aprils ago. Well done for running!! Well done for not being scared!! Well done, you strong girl!..