Sunday marks the anniversary of the publication in Turkey’s Official Gazette of the Turkish Surname Law, a controversial piece of legislation that has played a particular role in Turkification strategies within the country. The law stipulated that everyone living within the borders defined by the Republic of Turkey was obliged to have a surname.

Adopted on 21 June 1934 and ratified on 2 July, the law aimed to modernise Turkey by replacing traditional family names with surnames. It formed an integral part of Turkey’s broader nation-building project, seeking to unify the diverse ethnic and cultural groups under a singular Turkish national identity.

The implications of the law and the lasting impact it has had on the Kurdish population is still a subject of debate today.

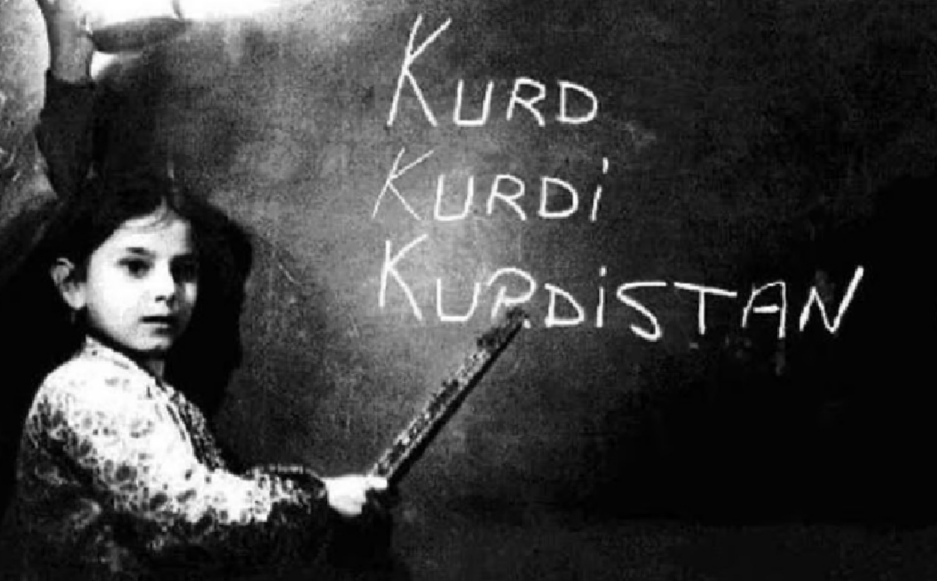

While the Turkish Surname Law affected all citizens, it significantly marginalised the Kurdish community. According to Kurdish historians, many Kurds were forced to adopt Turkish surnames, stripping them of their distinct Kurdish identities and further alienating them within Turkish society.

Critics argue that this was a denial of Kurdish identity and part of a broader strategy of Turkification employed by the Republic of Turkey. The aim was to assimilate ethnic minorities, particularly Kurds, into the dominant Turkish culture, effectively suppressing their unique language, traditions and overall Kurdish heritage.

How Turkey’s Surname Law restricted diversity

The implementation of efforts at Turkification, including the Turkish Surname Law, deepened existing tensions between the Turkish government and the Kurdish population. Over the years, these policies have been viewed as oppressive and have perpetuated social and cultural inequality, contributing to long-standing conflicts in the country.

Derya Bayır, a lawyer, researcher and expert on Turkish law, politics and society at Queen Mary University of London, explains the importance of the Surname Law in sense of Turkey’s assimilation policy by citing a speech by the then Minister of Internal Affairs Şükrü Kaya, saying:

“One of the highest duties of a country is to annex and assimilate all residents within it into its own society (bravo noises). We have experienced the opposite and the country fell into pieces. If the Ottomans had converted the residents of those places into their language and religion wherever they went, as happened in the early years, the borders of Turkey would still have started from Tuna … It is our debt to bring those who are resident here and within our society into Turkish society’s civilization and to ensure that they benefit from the enlightenment of civilization. Why should we still say Kurdish Memet, Cherkess Hasan, Lâz Ali? Above all, this shows the dominant element’s weakness. Whereas the Turkish element has assimilated [the others] the most. It is not correct to let these differences be. If somebody has a very little feeling of being different, let us erase this in schools and society. Then those men will be as Turk as I and will serve the country.”

The ‘Race Name Law’

The 1934 law that mandated the adoption of Turkish surnames was originally known as the ‘Soy Adı Kanunu,’ which literally translates as the ‘Race Name Law.’ The choice of the word ‘soy’ in its title was also significant since it means ‘race’, ‘ancestry’, or ‘breed’, according to Bayır.

The use of the word ‘soy’ indicated the legislator’s intention to enforce the adoption of names based on a person’s racial background. However, there were alternative words that could have been more appropriate, such as ‘known name’ or ‘family name,’ as used during the Ottoman Empire. A proposal was made by legislator Refik Şevket İnce within the Turkish Parliament’s Justice Committee to use the term ‘san adı’ (known name) instead. However, this proposal was rejected during the assembly general meeting.

The Surname Law was “in fact an attempt to achieve something beyond its claimed purpose of giving family names to people,” says Bayır and explains that the law’s aim of enforcing the adoption of Turkish words as surnames became obvious when it prohibited the use of ‘tribe and foreign race and nation names’ as surnames, since such a practice ‘without doubt’ would ‘impair the ideal of national management of diversity.

The Surname Law widens the cultural divide by imposing Turkish surnames on Kurds

The implementation of the Surname Law in 1934 included a provision that prohibited non-Turkish surnames, which was further elaborated upon in the Surname Regulations of the same year. Under these regulations, administrative bodies were granted the power to remove prohibited surnames without requiring a court decision.

Throughout the surname determination process, Kurds were consistently deprived of the opportunity to select their desired surnames. Furthermore, they were forbidden from having names in their own language, as the implementation of the Surname Law marked the initiation of a comprehensive ban on the Kurdish language.

While the law prohibited surnames that indicated ethnicity, individuals in the western regions of the country were granted the freedom to choose their surnames. However, in the predominantly Kurdish southeastern provinces, state officials began imposing surnames on individuals without their consent, utilising a predetermined list. It is important to note that many of the surnames imposed on Kurds highlighted Turkish ethnicity, including names such as Türk, Türkoğlu, Türkmen, Öztürk, Türkyılmaz and more.

The debate continues: Turkish court’s conservative stance on non-Turkish surnames

In the following periods, the Court of Cassation, Turkey’s highest court, adopted different approaches in various cases.

In instances of naturalisation, the court permitted new citizens to retain their non-Turkish surnames. However, when it comes to cases involving minority groups or religious conversions, the court has adopted a conservative and nationalist stance, rejecting non-Turkish surnames. This approach has received support from the Constitutional Court (AYM), which previously upheld the ban on non-Turkish surnames in a separate ruling.

One notable case involved Favlus Ay, a citizen of Syriac origin, who sought to change his name and surname to Paulus Bartuma. Ay’s chosen surname was prohibited by the Surname Law as it was not considered a Turkish surname. Ay argued that this prohibition violated the principle of equality as stated in the Constitution. While the initial court recognised the constitutional concern and referred the case to the AYM, the AYM ultimately rejected Ay’s demand in 2011, asserting that the law applied equally to all individuals and, therefore, did not violate the principle of equality.

The AYM justified its decision by emphasising that the prohibition on non-Turkish surnames serves to maintain national unity and protect the language and identity of the Turkish nation.

Kurdish community advocates for recognition and cultural heritage

On the anniversary of the law, Kurdish activists, scholars, and citizens have used the occasion to shed light on the ongoing struggles faced by the Kurdish community and to emphasise the importance of recognising and respecting their cultural heritage. They call for a greater understanding, inclusion, and coexistence between the Turkish and Kurdish populations.