Janet Biehl

The HDP’s unprecedented electoral successes in 2015, overcoming the 10 percent hurdle for parliamentary representation, was intolerable to the Turkish state. The following year the AKP, cracked down on the party, detaining and arresting numerous Kurdish politicians and activists on spurious charges of “terrorism.” Among the many arrested was Gültan Kışanak, the co-mayor of Amed. The arrests of so many talented, brave, and experienced people, men and women alike, was devastating for Kurdish politics and marked the onset of the process of criminalizing the HDP.

Once Kışanak was in prison, her friends suggested that she write her autobiography. After all, she had personally experienced the horrors of the Diyarbakir dungeon in the 1980s, then had emerged to become a brilliant force within the Kurdish movement as a journalist, editor, women’s movement activist, member of Parliament, and finally Amed co-mayor.

But instead of writing her own legendary story, Kışanak chose to turn to the many Kurdish women politicians with whom she had struggled on the outside and who now, like her, were imprisoned. She invited them to write essays recounting their own political biographies and experiences. The logistical difficulties of carrying out such a project while behind bars were enormous–the women were in prisons scattered across Turkey, and some were inaccessible. Ultimately Kışanak managed to collect the stories of 22 Kurdish women who had served as mayors, co-mayors, town councillors, and MPs.

To bind the essays together in a book, she wrote a detailed introduction that tells the story of women’s organizing within Kurdish and pro-Kurdish political parties in Turkey over the previous decades. The first Kurdish party, formed in 1990, had gender organization that was traditional: men made all the decisions and ran for office, while women did menial, clerical work if any at all. Party programs and speeches did not mention women’s issues or even address women as voters.

Kışanak’s introduction recounts how Kurdish women changed this situation. (She does not claim to cover the huge topic of women’s organizing outside the party, while acknowledging its significance.) They had to fight patriarchy and its mentality within the party. Their men colleagues held women to impossible standards and assured them that men in the constituencies would never vote for women as leaders. But women persisted, overcoming their self-doubts and learning how to struggle. Through painstaking, relentless work, they organized committees, branches, commissions, and other internal party structures They achieved a women’s quota for party positions, a ban on polygamy among party leaders, and even a budget. They achieved dual leadership for executive positions, with men and women co-chairs at all levels.

Once women stepped forward to run for office, the results varied, and while a man candidate who lost an election escaped blame, a woman candidate who lost faced the wrath of her male colleagues, who blamed her exclusively. But armed with the gender quota, women kept recruiting candidates and meeting with local women. Ultimately they proved that women could not only win elections but be re-elected. Then they extended the concept of co-chairing (for executives within the party) to co-mayoring (for executives within local government) and implemented it in 2014. That year numerous women were elected as co-mayors. Once women were in office, it had become clear, many voters preferred them. Rather than serving powerful interests, women officials tended to serve the people and work to improve people’s lives. They hired women for their staffs and developed programs for women. Suddenly local women had a place in town halls.

This enormous advance came to an abrupt end with the arrest wave of 2016. Still, it was a remarkable evolution over the course of only twenty-four years. Kışanak’s introduction is the first time I have seen the story told in detail in English, and it is well worth reading. The essays are stories of women who brought about this change in particular places, recounting the particular challenges they encountered and victories they achieved. The book was published in Turkish in 2020.

Over in the United States, the book caught the eye of Ruken Işık, a Kurd originally from Bakur, who was then working for her Ph.D. at the University of Maryland. (She is currently a lecturer at American University in Washington, D.C.) Isik realized that the book must be published in English, so she joined forces with Emek Ergun, a global studies and women’s studies professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Since the original book had been a collaboration among women, Isik and Ergun decided that the translation must be a collaboration among women as well. For each of the 22 essays, they recruited a different translator. They invited me to participate, even though I don’t know Turkish, because of my forty years of work for the U.S. book publishing industry. Clearly 22 essays, each with a different author and translator, would need some editing for consistency.

To organize the team, Işık and Ergun developed a timetable and a process that involved common workshops and a shared dictionary. The translators shared questions and problems in a common internet platform, and once they had drafts, they paired up and exchanged them for peer review. After the 22 essays were in English, I edited them. I also drew a portrait of each contributor—they’re included in the book.

The obstacles that Kurdish women faced and overcame will inspire women fighting patriarchy around the world. Their courage and persistence remain extraordinary, since by struggling for women’s freedom in Turkey, they risked brutal imprisonment. While some have since been released, others, including Kışanak herself, remain behind bars. For their sake and for the sake of women everywhere, I hope this book finds a wide readership.

–Janet Biehl, October 20, 2022

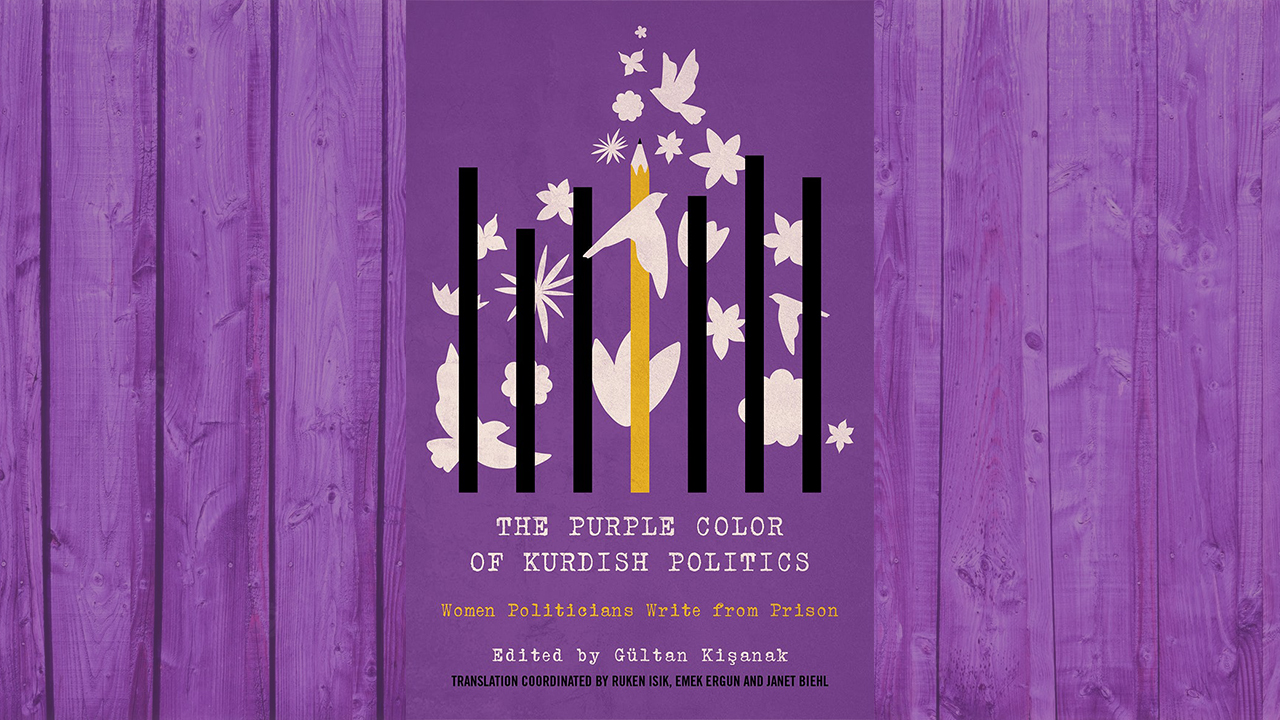

The Purple Color of Kurdish Politics: Women Politicians Write from Prison. Edited by Gültan Kışanak, prepared for publication by Ruken Isik, Emek Ergun, and Janet Biehl. London: Pluto Press, 2022.

Janet Biehl (b. 1953) was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, and educated at Wesleyan University and the CUNY Graduate Center in New York. She works as a freelance copyeditor for major book publishers and is also a translator and pen-and-ink artist.