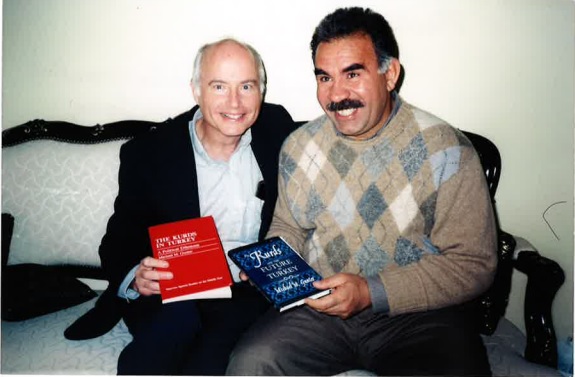

Michael Gunter

Less than a year before Turkey captured him in February 1999, I met Abdullah (Apo) Öcalan in Damascus in March 1998. I first saw him with some others in an apartment a couple of rooms away, but recognised him immediately. As an academic who had been writing about the Kurds in Turkey sympathetically since the mid-1980s, several years before most others in the West developed their interest, I was invited by the PKK authorities to visit Öcalan after making a number of enquiries about doing so.

I was met at the Damascus airport and taken to a hotel for a rest. A few hours later I was taken by car via a circuitous route to my destination. Presumably, the roundabout way was to prevent me from knowing exactly where I was going. On our first meeting, we ate with several others in the Damascus apartment. Ali Qazi—the son of the famous Qazi Mohammad who had been president of the Mahabad Republic in Iran in 1946—served as the translator. Unfortunately, we needed a better translator. Nevertheless, I liked Ali Qazi very much and through him did get to converse with Apo on many topics.

My second meeting with him took place a short distance outside of Damascus, in a nondescript structure off a main highway. Inside the walled compound, I found a surprisingly impressive villa and garden. Armed guards kept watch from the roof of the villa. Attached to the villa compound was another, larger, walled compound containing simple living quarters for some 170 male and female fighters, an open green area, a cemented athletic area, and a life-sized gilded statue of Mahsum Korkmaz, a PKK commander killed earlier in combat in 1986.

Each of my meetings with Öcalan lasted for some six hours and included lunch. I found the Kurdish leader an engaging and polite host. During lunch breaks, for example, he showed me the pigeons he kept. He also let a honey bee alight on this finger and mused how it was “half sweet and half poison”. On my second day, I was invited to play volleyball and football with him and his followers. When formally posing for a picture, Öcalan turned deadly serious and rather wooden, but at other times he smiled easily. His conversations were often very animated. He showed a surprising knowledge of international tennis stars, deeming Andre Agassi his favourite. He told me that he admired tennis because “it involves strategy as well as strength and power”.

In our first meeting, Öcalan spoke in Kurmanji, a Kurdish dialect I was told he had recently learned to speak much better. The second day, he spoke in Turkish. When I asked him why he was fighting against Turkey, he replied, “In Turkey, they say there are no Kurds, that they don’t exist. The government say this. Even the professors at universities say this. The Turks only accept the Kurd who denies he is a Kurd. Only a dialogue between Turkey and its Kurds can get the victims out of this continuing trap.” Twenty-five years later, I think progress has been made because Turkey no longer denies the existence of the Kurds. The problem now is what should the Kurds’ position be in Turkey?

When I asked him how he had been able to keep up the fight so long, a question still very valid 25 years later, Öcalan told me, “Anyone who thinks as a Kurd in Turkey is with the PKK. If Turkey finishes the PKK, then it will have only the wall to talk to. I use Turkish stupidity to build a Kurdish movement. This is very important. Turkey’s harsh, ignorant treatment of the Kurds has helped give birth to a greater sense of Kurdish nationalism. I use Turkish mistakes to build up my power.” Twenty-five years later, Öcalan’s words still ring true.

Finally, when I asked the Kurdish leader what type of settlement he sought with Turkey, he declared, “I accept the current Turkish border. Nobody wants Turkey to be divided. This is very important. I want to negotiate a just, democratic solution to this struggle. The Turks must accept the Kurdish identity. They should say in the constitution that there are other people in Turkey and accept a federal system, as in the United States, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, and Spain.” Then Öcalan surprised me when he added, “If Ataturk were alive today, he would not act like the Turkish leaders are now. He would see the bankrupt result of his policy and change it.” Of course, this was just speculation, but I have always thought that if Turkey and its Kurds could agree on some important constitutive principles and symbols like this, it might help lead to the settlement both want.

•

Turkey captured Öcalan in February 1999. He has been held in prison since then. For the past 31 months, the Kurdish leader has been held incommunicado. Apparently, the Turkish authorities believe that this type of treatment best serves their purposes. It does not. Indeed, a decade ago, the Turkish government was actively negotiating with Öcalan during the period known as the Democratic or Kurdish Opening. The Turkish authorities even announced that Öcalan was a responsible interlocutor with whom to negotiate. There was even serious talk about releasing the Kurdish leader to some type of house arrest.

However, the negotiations between Turkey and the PKK began to bog down as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan apparently expected the PKK to be satisfied with just a process of negotiating, while the PKK sought specific agreements recognising specific Kurdish political, social, and cultural rights. The Kurdish Opening was closed after the HDP won enough seats in the parliamentary election of June 7, 2015 to deny Erdoğan a new majority in the Turkish legislature. At this point, the Turkish president calculated that his renewed electoral success depended upon assuming a strong Turkish nationalist position. This required closing the Kurdish Opening and turning to the ultra-nationalist Turkish MHP for support. Erdoğan calculated that he could win more votes by assuming an anti-Kurdish position than by appearing to be sympathetic with Kurdish views. He was correct! But only at the cost of peace. Öcalan continuing incarceration incommunicado was the added price to pay.

•

Indeed, one of the main reasons Erdoğan was reelected president in May 2023 despite the disastrous Turkish economy, the tragic earthquake in February 2023 with its excessive casualties, and body blows to the very concept of Turkish democracy and the rule of law—all in part due to his incompetence—was Erdoğan’s verbal assaults on the Kurds. Erdoğan accused his main opponent Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu of having ties to Kurdish terrorists, even showing fake videos at campaign rallies of PKK leaders singing the opposition’s campaign song. He reminded the public of the continuing civil war across the southern border in Syria, and how the United States was in effect supporting the Syrian Kurds, while shutting its NATO ally Turkey off from its new F-35 jet planes as well as earlier F-16s. He prominently used religious, nationalist rhetoric promising to make the country great again as a regional and even a global military and industrial power.

In a major, joint interview with the pro-government ATV/A Haber TV and Sabah newspaper that was published on the official Turkish government website, Erdoğan sought to gain voter support with inflammatory, anti-Kurdish rhetoric when he claimed that Kılıçdaroğlu and his supporters “easily continue their cooperation with the extensions of the separatist organisation. . . . Were they ashamed to stand side by side with those chanting slogans such as ‘blood for blood, revenge vengeance” in their rallies in Van? . . . Of course, not only him [Kılıçdaroğlu], but also those with him do not hesitate to be associated with terrorists. . . [and he] reveals his love for terrorists. . . . He has filled the CHP administration with terrorist lovers.”

Erdoğan also declared that if Kılıçdaroğlu won he would release the jailed, former HDP leader Selahattin Demirtaş. “Now this Selo (Demirtaş’ nickname) is a terrorist who killed 51 of our Kurdish brothers in Diyarbakir, he is currently serving his sentence. What does Kılıçdaroğlu say? He says if you want to remove it, you will vote for me.” During this same tirade, the Turkish president also declared that, “If you want to learn the lesson of lying, go to Mr. Kemal. . . . Now he vomits hate to anyone who comes before him, including earthquake victims. . . . Today they use the language that makes the Nazis look like a candle, they have gone this far.” Kılıçdaroğlu’s more conciliatory position was not able to overcome this anti-Kurdish poison.

Even after the election, Erdoğan persisted in using demeaning, anti-Kurdish language against his opponents as illustrated by his statement that the main opposition CHP had permitted the PKK “to control its underwear.” In the Turkish context, this metaphorical expression carried a deeply derogatory connotation, implying the loss of dignity and association with prostitution. Erdoğan was crudely portraying his opponents as weak, subservient, and lacking in moral integrity.

Despite Erdoğan’s spiteful words, I think that almost a quarter of a century after I visited him, Öcalan would be very proud of the Kurdish women and men who have followed the cause he so prominently began. The Kurds have constructed an even stronger organisation than they had when Öcalan was still free, based more on the green light of justice than mere violence. Of course, mistakes have been made, but when you look at the history, Öcalan told me you will see that the real terrorist has been Turkey.

So today, almost 25 years since his capture and continuing incarceration incommunicado, it is time for Turkey to release the Kurdish leader. Then we can begin to test his willingness and ability to negotiate a just peace for both sides as Nelson Mandela did 30 years ago in South Africa. What does Turkey have to lose? If Öcalan is not up to the task, Turkey can always continue its current, barren policies.

Michael M. Gunter is a professor of political science at Tennessee Technological University and the secretary-general of the EU Turkey Civic Commission (EUTCC). He has written more than 20 peer-reviewed scholarly books and 150 articles over the years.