Since Syria turned into an international battleground after the civil war began in 2011, the reports of independent journalists – most of whom were actually working as volunteers in the country – have become precious in understanding what has been happening, since there has been a lot of disinformation that has been generated by media outlets embedded with or even directly linked to powers that have interests in the war.

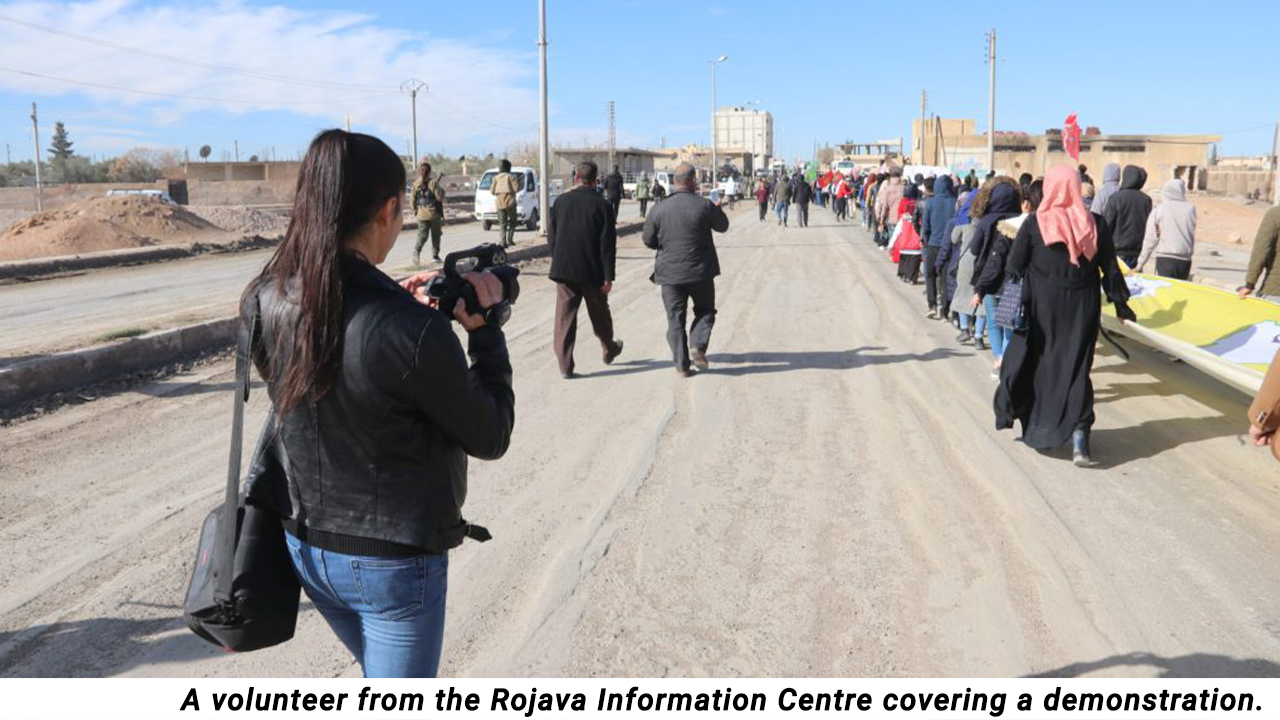

Reportage of what has been happening since 2016, in the areas under the control of the Turkish army and its affiliated armed groups in north and northeast Syria, has significantly been influenced and controlled by Turkish state linked propaganda outlets and channels. Several international media outlets, consciously or otherwise, have reported almost exclusively through the propaganda laden lens of the Turkish state and linked media outlets, contributing, in the opinion of several investigative reporters and journalists, to the circulation of problematic and misleading news. This institutionalized distortion of the facts were countered, first by individuals working in the field as volunteer journalists, then through their coordinated efforts. The creation of the Rojava Information Centre (RIC) by the end of 2018 was a result of such concerted efforts.

Chloé Troadec, a French volunteer at the RIC, spoke to Chris Den Hond, and described what she and other volunteers were faced with in North East Syria as the region was affected by successive military operations by Turkey which led to the take-over of areas.

Medya News shares the first part of the translation of the interview, originally published in French on 6 August by Roj Info. The translation has been edited by C. Baraldi.

Chloé Troadec is an international volunteer at the Rojava Information Centre, located in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), in Rojava.* The Centre produces information from the field, press releases and constantly updated files. Many of the local journalists have paid for their commitment with their lives. Chloé Troadec explains what the duty to inform is, in this area where Turkish and Turkish-affiliated and sponsored militias have taken control.

Why did you go to Rojava?

Why did you go to Rojava?

In the university, I had Kurdish friends who explained to me the Kurdish reality and in particular, Rojava’s reality, the Syrian Kurdistan. It was during the Battle of Kobane, and there was a lot of discussion about the political project in Rojava, and about the role played by the men and women of the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) in the fight against the Islamic State [ISIS].

I decided to go to Rojava to see for myself what was happening. There, I met other volunteer journalists, Thomas, Joan and Connie, and we all found out that especially after the Afrin massacre, there was a huge problem of media coverage in the international press. In fact, all the journalists of the major international media were gathered at the Turkish border, on the Turkish side of Afrin, and we were outraged to see how much they believed the Turkish propaganda.

“I can confirm that it has never been SDF’s tactic to attack Turkey from Syrian soil. Turkey was spreading this propaganda to justify its attacks on Rojava.”

Chloé Troadec

They picked up dispatches from Turkish agencies like Anadolu Agency [the Turkish state news agency] almost word for word. They had no knowledge of what was happening in the Kurdish region of Afrin, which was almost exclusively Kurdish before the Turkish invasion. There was also a problem on the Kurdish side: a lot of information was gathered, but very little in European languages, and it was sometimes considered as propaganda. This information was often directly circulated by the Autonomous Administration of Rojava and was not taken seriously by the international media.

It is very hypocritical, because they considered the news of Anadolu Agency, which is directly linked to the propaganda of the Turkish state, as a reliable and serious source, unlike the Kurdish media. So we started to learn the Kurdish language and developed the Rojava Information Centre (RIC), which became an information production centre. We heard that one of our files landed on Mike Pence’s desk at the White House. I believe there was an impact somewhere at the highest level of power in the United States, and probably in other states as well.

Some concrete examples?

News organisations themselves had difficulty accessing information on the Syrian side, and tended to believe the Turkish media, which has experience in generating false information. One of the biggest lies they were spreading goes back to the Afrin Operation. Turkey had just bombed a civilian hospital. They later released a video claiming that the explosion targeted and destroyed the building next to this hospital. We managed to do a geolocation which proved the opposite: the hospital was indeed the target. We personally attended the scene to confirm this information, but the video remained online.

Another example of Turkish disinformation was stating that the YPG (People’s Protection Units) were carrying out attacks on the Afrin border against Turks, including civilians. The same thing was done during Turkey’s attack on Serêkaniyê and Tal Abyad. However, the BBC has shown that there were actually very few YPG and Syrian Democratic Forces [SDF] attacks on the Turkish side of the Turkish-Syrian border. I can confirm that it has never been SDF’s tactic to attack Turkey from Syrian soil. Turkey was spreading this propaganda to justify its attacks on Rojava.

“The authorities in the region do not intervene in our work. They understand very well that we are here to speak on behalf of the people in North Eastern Syria. We are financially, politically independent, and so is our information.”

Chloé Troadec

Can you work and move freely in North East Syria?

The authorities in the region do not intervene in our work. They understand very well that we are here to speak on behalf of the people in North Eastern Syria. We are financially, politically independent, and so is our information. We get money when we work as fixer/translators for international media; agencies pay us for our photos or videos; so yes, we have our own income, and the expenses are not huge. We don’t have a salary, we are volunteers. Life in Syria is not expensive at all.

How did you get this credibility with big media institutions like the BBC and Associated Press?

When we saw this lack of reliable and objective information at the time of the invasion of Afrin, we tasked ourselves with the goal of having the facts reported without distortion. In Afrin, before the Turkish incursions, the population lived relatively in peace, with a level of security and democracy; women’s rights and human rights guaranteed. Afrin hosted many internal Syrian refugees. In short, before the Turkish invasion, Afrin was the safest and one of the best places to live in Syria.

We investigated and then claimed that the invasion of Afrin was a violation of international law, and that appalling war crimes were committed against the civilian population. Many young Kurdish women were kidnapped, raped, disappeared, and some committed suicide in prison after being raped by pro-Turkish jihadists or Turkish agents. We were aware of these horrifying facts.

“Our work is not without danger. In Baghouz, a translator and a driver were killed by a mine. It happened after clashes. Being on the front lines isn’t always exciting.”

Chloé Troadec

The Rojava Information Centre was created in the fall of 2018 and we officially started in January 2019. Quite quickly, we acquired some media notoriety. We often did interviews that were eventually available for the international media, or helped with translations or finding relevant people to interview. Therefore, when Turkey invaded the Tal Abyad – Serêkaniyê region in October 2019, we were already well positioned. In short, we provide foreign journalists and NGOs a service with our work, and we produce information ourselves. There are mainly files, for example on Afrin or the political system in northeastern Syria. All of this requires several months of research.

So are you often in the field?

I was in Baghouz, the last ISIS enclave in Deir Ez-Zor, for a month and a half, to cover the clashes there for the RIC. All the international press was there. CNN had a truck with six journalists, the BBC, other agencies. (…) At that time, we built good links with the journalists. Afterwards, it allowed us to become a reliable source of information for them. (…) Our work is not without danger. In Baghouz, a translator and a driver were killed by a mine. It happened after clashes. Being on the front lines isn’t always exciting.

There were whole days and even weeks when nothing happened, because, for instance, negotiations were taking place. On the other hand, during these periods of relative calm, we preferred to follow the women and children who left the camp to go to the SDF. These interviews have revealed a lot to us. There were ISIS women, but also a lot of Yazidi women who had become slaves. When members of the YPG and YPJ asked in Kurdish, “Are there Yazidi women here?,” some answered in Kurdish, “Yes, me!” These moments were dramatic because these women had been, since 2014, therefore for five years, slaves in the hands of the Islamic State. They came out of it in a state of severe psychological trauma; sometimes with 12-year-old children born in Shenghal (Sinjar) and captured with their mothers. In the evenings, we often spent hours sorting through photos and posting testimonials, going online despite a very poor internet connection; testimonials which were also broadcast in the international media.

* Historically, Rojava means ‘Western Kurdistan’ or ‘Syrian Kurdistan,’ consisting of three cantons: Afrin, Kobane and Cizire (with Qamishlo). With the loss of Afrin and the conquest of Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor, a territory now under the protection of the SDF, the region is no longer a predominantly “Kurdish” territory, but home for different peoples where the Autonomous Administration (AANES) tries to practice the principles of a system called “democratic confederalism.” It must also be noted that the YPG had actually, from the beginning, positioned itself politically against the foundation of a new nation-state and fought for a democratic political system where “living together” is promoted.