Sarah Glynn

On 15 August, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party – the PKK – marked 38 years of armed struggle against the Turkish state. The decision to take up arms is not one made lightly. It is a last recourse when all other options have been thwarted. 38 years on, the Turkish government continues to employ all its powers to close down any possible political route to Kurdish cultural freedom and to crush any emergence of Kurdish self-organisation, even outside Turkey’s borders. This week has seen further crackdowns on Kurdish politicians and activists in Turkey, and more fatal attacks aimed at destabilising the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. It has also brought further political discussions that have alarming echoes of 1998, when Turkey forced the Syrian government to agree to expel Abdullah Öcalan and the PKK.

Blocking the political option

The Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) is a standard bearer for the political solution to the Kurdish question as well as for a fairer society all round. Thousands of party members are in prison, including its former co-chairs and former members of parliament and mayors. Almost every elected HDP mayor has been deposed and replaced by a government appointee. Ongoing court cases threaten to sentence leading party members to life without parole, and to shut down the party completely. Every week, more party members are rounded up and detained. It is a testimony to the commitment of members and supporters that this has been happening so consistently for so long, and yet the party goes on, and more people have stepped up to take the place of those who have been locked up or forced to flee the country.

This week, Firat News Agency reported a “new wave of repression against the HDP” with detentions in Amed, Hakkâri, Adana, Mersin, İskenderun, Erzin, Manisa, İzmir and Van.

Anyone arguing for Kurdish rights can find themselves facing charges of terrorism on the flimsiest of excuses. An indictment just issued against 11 HDP members includes as evidence that they listened to Kurdish music at events.

Once in prison, politicians and activists cannot even expect to be granted a normal entitlement to conditional release. Keeping political prisoners beyond their release date has become an increasingly common practice. On Tuesday, it was reported that Mukaddes Kubilay, the former co-mayor of Ağrı, who was due for release on 4 August, was being kept behind bars because she was “not in good conduct and her conditional release would not be appropriate.”

There has been a long line of prison deaths, many of which can be attributed to poor and abusive prison conditions, or to more suspicious circumstances. Seriously ill prisoners are kept behind bars even when medical advice demands their release. This week, three more politicians died in prison. On Sunday, İbrahim Yıldırım, of the HDP-linked Democratic Regions Party (DBP), who had multiple medical problems, died in Elazığ High Security Prison 12 days before he was due for release. On Monday, Mehmet Candemir, Former Provincial Co-Chair of the DBP in Batman and Party Assembly Member, died in Giresun Espiye L Type Closed Prison. His family was told that he had suffered a heart attack. And on Thursday, the former mayor of Gogan, Bazo Yılmaz, also kept detained despite being seriously ill, died in T Type Prison No. 2 in Riha.

Relatives of sick prisoners are regularly attacked by police at their weekly protests against the mistreatment being meted out in the prisons. A week ago, in Istanbul, when they attempted to give a press statement, 27 people, including two children, were detained and held in handcuffs for 5-6 hours. Police stood on their necks and hit them over the head, and one of the children was subjected to a strip-search.

Destabilising North and East Syria

In North and East Syria, where the Kurds and their neighbours have established an autonomous administration that respects people’s rights to practice their own culture, as well as promoting women’s rights and grassroots democracy, Turkey is intensifying its attempts to destabilise and destroy all that has been built, and to force Kurds out of the region altogether. Although they have been refused permission for a full-scale ground and air attack by Russia and the United States, who control the airspace, Turkey has continued their intensified bombardments.

On Tuesday, a drone strike on a post manned by the Autonomous Administration’s Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) killed five and wounded two; while 24 hours of shelling on numerous villages caused injuries and forced displacement. Attacks on the symbolic city of Kobanê, which turned the tide against ISIS, killed a child and left others wounded. On Thursday, a Turkish drone hit a special education centre for girls near Tal Tamir, killing four children and wounding eleven more. The centre was sponsored by the UN, and is situated just 2 km from a US-led Coalition base.

Turkish bombing also killed sixteen Syrian government soldiers stationed on a hill west of Kobanê, and injured three others.

At the same time, Turkey’s constant invasion threats make any sort of settled life impossible, as hundreds of thousands of people are kept on tenterhooks in fear of imminent attack. Rumours of invading forces can quickly find purchase, and this proved especially true on Tuesday, when mosques in Gaziantep’s Karkamış district, near the Syrian border, put out what appears to have been an unauthorised announcement that people should stay at home in anticipation of imminent action by the Turkish army.

The SDF has retaliated to Tuesday’s attacks with three cross-border operations against Turkish forces, in which they claim to have killed seven Turkish soldiers and injured at least three others.

A new deal with Syria?

President Erdoğan takes a bullying approach to diplomacy and has shown no hesitation in making and breaking alliances to suit his current needs. Much discussion is now focussed on the possibility of an abrupt turn on Turkey’s relationship with Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian government, which would need to be accompanied by a reversal of support for the Islamist opposition militias that have thrived under Turkish backing. While some sort of rapprochement with Assad has long been under discussion, this has quickly acquired a general political acceptance. However, any agreement would be far from easy, and would open possibilities for a lot more violence.

Under Russian tutelage, the basis and justification for such an agreement would be the so-called Adana Agreement of 1998.

In the 1980s and 90s, relations between Syria and Turkey were tense. While Turkey was part of NATO, Syria was aligned with the Soviet Union, and this fundamental division was deepened by a dispute over Hatay Province (which Syria considered to have been illegally ceded to Turkey during the French mandate in the 1930s), and by disputes over Turkish overuse of the water of the Tigris and Euphrates. In this atmosphere, although Syria oppressed its own Kurdish population, they welcomed the PKK to establish camps within their borders.

In September 1998, almost a decade after the end of the Cold War, Turkey threatened to invade Syria if the Syrian government didn’t expel the PKK and hand over the PKK’s leader, Abdullah Öcalan. Öcalan left Syria in a search for asylum that ended, five months later, in his CIA-backed abduction from Kenya. And on 20 October, eleven days after his departure, the Syrian government, then led by Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez, signed an agreement in the Turkish city of Adana. In return for better bilateral relations, Syria agreed to recognise the PKK as a terrorist organisation and to prevent all PKK activities within Syrian borders. Annex 4 of the agreement is not in the public domain, but is quoted, in a letter from the Turkish Foreign Minister to the European Commission, as saying “The Syrian side understands that its failure to take the necessary measures and security duties, stated in this agreement, gives Turkey the right to take all necessary security measures within 5 km deep into Syrian territory.”

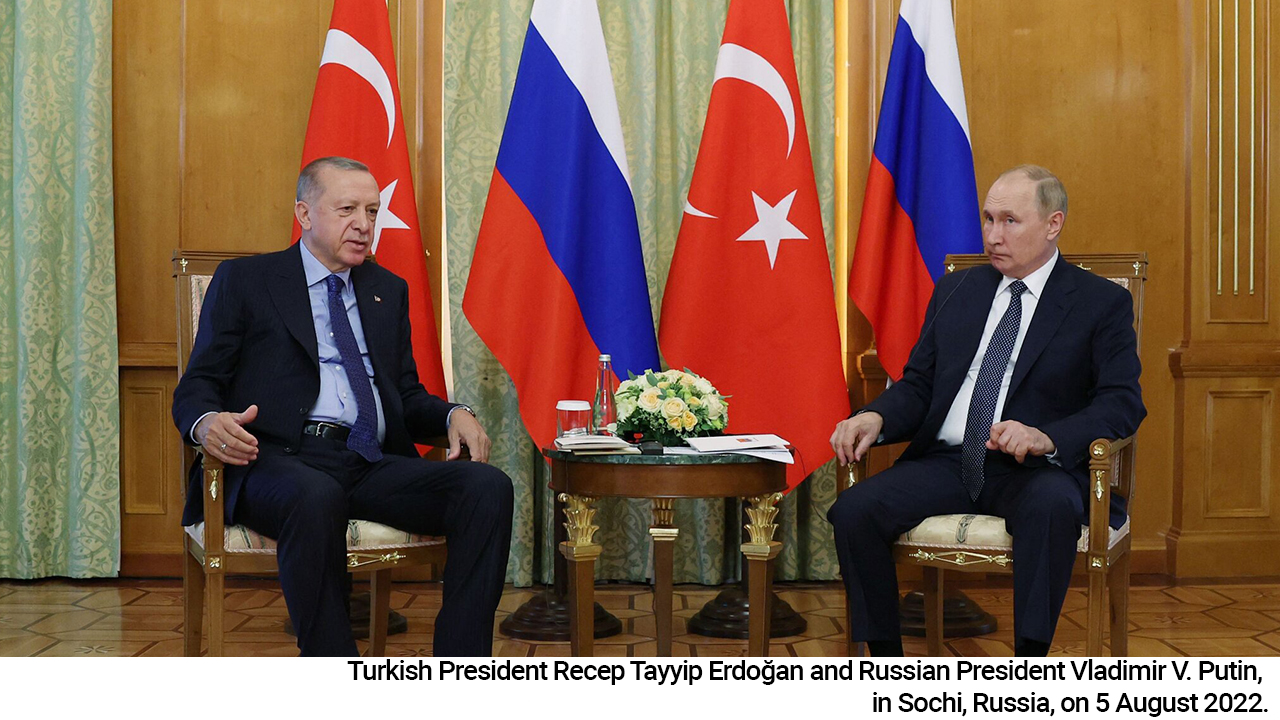

A revised Adana Agreement was mooted by Putin in January 2019. The Assad government insisted that this would have to be dependent on Turkey ending its support for the opposition militias and withdrawing its own forces. That October, the Memorandum of Understanding agreed by Putin and Erdoğan in Sochi, which established a ceasefire to end Turkey’s last invasion, stated that “Both sides reaffirm the importance of the Adana Agreement. The Russian Federation will facilitate the implementation of the Adana Agreement in the current circumstances.” However, as Fehim Taştekin pointed out at the time, “Erdoğan’s perspective of the Adana accord seems to differ from that of Putin.”

Following the most recent meeting between Erdoğan and Putin, on 5 August, Amberin Zaman and Sultan al-Kanj, writing in Al Monitor, have described growing official support in Turkey’s ruling circles for engagement with the Syrian government, including backing from the government’s de facto coalition partner, Devlet Bahçeli, leader of the far-right National Movement Party. They point out that this approach apes the long-held position of Turkey’s main opposition and is a prerequisite for the return of Syrian refugees, whose presence has been allowed to breed increasingly violent resentment. They also note that, following the July meeting in Tehran between Turkey, Russia, and Iran, Erdoğan moved from calling on the United States to end their support for the SDF, to echoing the demand of Russia and the Syrian Government that the US leave Syria altogether. They quote Saleh Muslim, co-chair of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the main political party in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, who told them that “We have to take these moves seriously because the sides (Assad and Erdoğan) are taking their orders from the same place — from Putin … The fact they are aligned against the Kurds is no surprise to the Kurds.”

However, there is still a big divide between government thinking in Syria and in Turkey. While Turkey insists that the SDF is synonymous with the PKK and must be eliminated, the Syrian government wants to see the SDF break ties with the United States and give up hopes of autonomy, but would like to see this powerful military force integrated into the Syrian army. The people that Syria regards as terrorists are the Islamist militias that have benefitted from Turkish backing, and which will resist any agreement between the two governments.

Fehim Taştekin, also in Al Monitor, points out that Turkish expectations are still very far from what Assad would consider acceptable. He characterises the emerging Turkish government view as wanting cooperation to destroy the autonomy of North and East Syria while making this conditional on no legitimisation of the SDF; wanting Damascus to facilitate the return of Syrian refugees, while maintaining the existing Turkish demand that the SDF be kept out of a 32km border strip; wanting opposition elements who have fought against the regime to be included in a future political settlement; and drawing up a “revised Adana Agreement” that would give Turkey the power to pursue the “PKK” – under which heading they include the SDF – 32km into Syrian territory.

Researcher Faik Bulut, interviewed for Bianet, characterises Syrian government conditions for any agreement as the withdrawal of Turkish forces; an end to Turkish support for the jihadist groups and opposition militias; and a demonstration of Turkish sincerity.

Finding agreement between Turkey and Syria is not only extremely difficult, it is only part of what would need to be addressed. Turkish support for ISIS and for other Islamist militias has turned the region into a hornet’s nest of potential problems. As has been repeatedly emphasised, ISIS still maintains numerous cells – especially in the Turkish occupied areas, which provide a safe haven – and these are waiting for any opportunity to affect a mass breakout of ISIS prisoners and rebuild their strength. Despite all the warnings, little has been done to provide international support to guard the prisons and camps, and ultimately to put the prisoners on trial and to disperse them. The SDF are fully stretched, and if they are called upon to defend an attack on the Autonomous Administration, they will not also be able to guard against an ISIS escape and resurgence.

And it is not just ISIS that is ready to carry out violent attacks. Other Turkish-backed militias share similar violent interpretations of Islam and predilections for extreme misogynist violence. Often, they also include former ISIS members. They will not sit back and allow Turkey to take away their power. All these groups present risks of extremist violence in Syria and Turkey, and beyond. Any attempts to bring the areas controlled by the opposition militias back under the Syrian government could also encourage a new wave of emigrants. Erdoğan is not averse to taking risks, and every possible scenario is risky, but this is an especially risky strategy for the run-up to an election.

Perhaps, at this stage, Erdoğan simply wants to be seen to be making moves towards a solution that would still allow him to target the Kurds, and to put a positive spin on Turkish adventurism in Syria. However, yesterday, on the plane back from Kyiv, he told reporters that there was a “need to take further steps with Syria”, and claimed, despite all the Turkification that has taken place in the occupied areas, “We do not have eyes on the territory of Syria because the people of Syria are our brothers”.

Turkish diplomacy is often belligerent, but this week’s fatal attack on Syrian troops is not perceived as the best opener for greater dialogue.

New-old imperialisms

I have related the situation now to events in 1998 and also 1984, but today’s imperial conflicts can also be understood as a continuation of the conflicts that erupted in the First World War, and of the attitudes that produced the treaties that drew today’s contested boundaries and divided Kurdistan. Other recent events suggest that international politics has learnt little since that time.

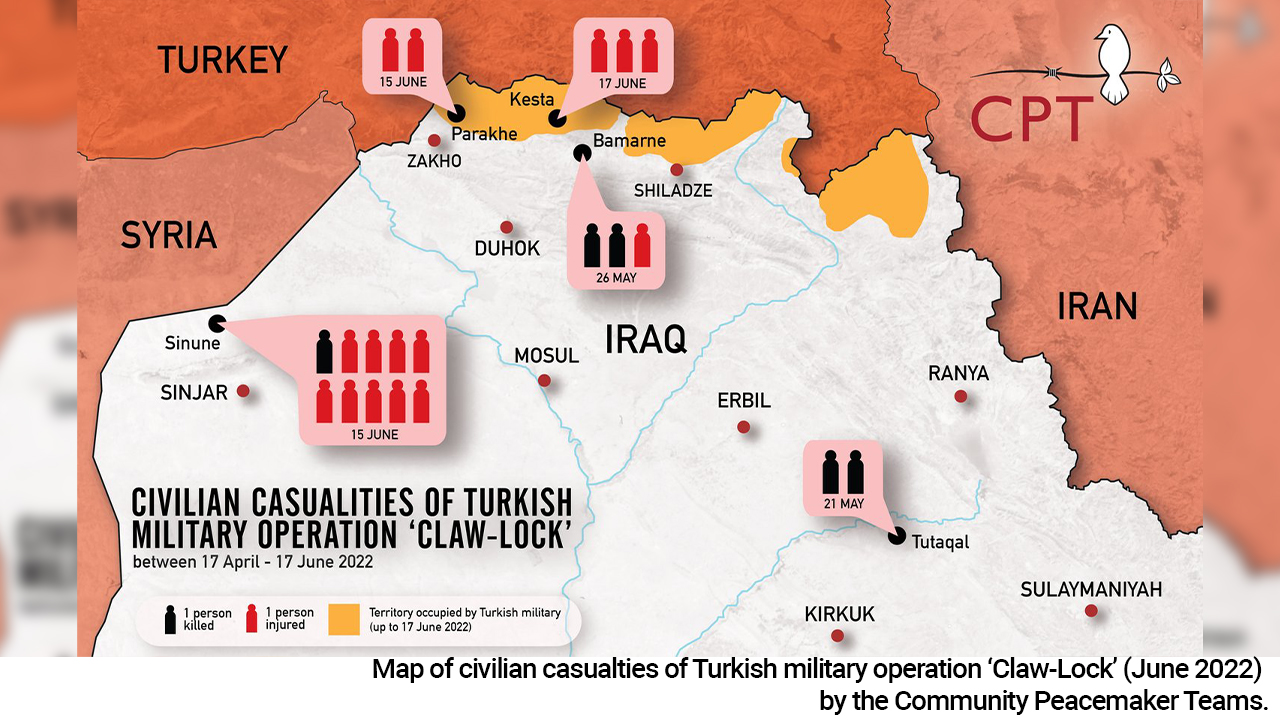

Turkey’s incursions into the Kurdistan Region of Iraq have been given even less attention by international powers and media than their ceasefire-breaking attacks in Syria. Kurdish sources claim that Turkey itself is hiding what is happening as they don’t want Turkish citizens to be aware of the extent of their casualties. Firat News Agency reports that dead soldiers and village guards are being denied military honours or any public announcement of their deaths.

Turkey has posed as a leading defender of Palestinian rights, publicly breaking diplomatic ties with Israel – though they always maintained strong trade links. On Wednesday, as part of another U-turn, Turkey announced that full diplomatic ties with Israel would be resumed. This announcement came after a week when Israeli attacks on Gaza had left 49 dead, including 17 children.

Despite its social-democratic legacy, Sweden is showing itself far from immune to the politics of power and money. Swedish Daily, DN, has reported on a deal that will see the Swedish state subsidising a large railway project in Turkey, which is likely to result in Swedish money funding the friends and supporters of Erdoğan and Putin.

Meanwhile, a young Kurd, Zınar Bozkurt, has been taken to a Swedish detention centre to be deported back to Turkey. Bozkurt was active in the HDP youth section in Turkey before fleeing to Sweden to escape the risk of a prison sentence. The decision to deny him asylum, and accept the assessment of the Swedish security police that he posed a security threat, was made two years ago. The process is opaque, and reports suggest that at least 40 others are in a similar position. Sweden was already conceding to Turkish pressures long before Turkey exploited their power of veto over Sweden’s application to join NATO.

In Germany, a parliamentary question from Left Party MP, Gökay Akbulut, produced the information that 13 immigrants have been banned from politics through a controversial, and loosely worded law that is known by the name of the Kurd on whom it was first applied. Six of the 13 are Kurds.

The United States sees its own best interests in not crossing Turkey. Even when the Senate Foreign Relations Committee responded to “troubling reports of increased drone & other attacks into Northeastern Syria”, their tweet made no mention of who sent the drones. Their comment that “The U.S. and its SDF partners must continue to ensure ISIS cannot rebuild itself in Syria” rings hollow when nothing is done to stop Turkey’s attacks. Tweets put out by the US-led coalition condemning attacks on civilians never name Turkey. They call for de-escalation by “all parties”, as though civilians, such as the dead schoolgirls, should be blamed for getting hit.

If international powers have learnt nothing, political activists cannot afford to be so ignorant – especially now that climate change and new weapons have made the stakes even higher than they were last century. The solutions being implemented in North and East Syria are important not just for the people there but for helping to reconfigure a genuinely sustainable world. There are some signs of fight back against the old imperial politics – not least in the United Kingdom, where the trade union movement is currently rediscovering its purpose and power – but different struggles need to be linked and to be imbued with a vision of what they are fighting for, as well as what they are against. The Kurdish struggle has an important role to play in the struggle for humanity’s future.

Sarah Glynn is a writer and activist – check her website and follow her on Twitter.