“When the party in power is the one that gets to conduct purges of a nominally independent civil service, ignore the rulings of regulatory bodies and appoint the judiciary that will imprison their enemies on flimsy pretexts, elections may be important for all the wrong reasons,” writes author and translator Izzy Finkel in a recent article for the London Review of Books. And she adds: “They shouldn’t have to matter this much.”

Turkey’s pivotal parliamentary election held on 14 May resulted in a victory for the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) led bloc, while the presidential election reached a runoff on 28 May as no candidate secured an absolute majority. Incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan emerged as the front-runner, garnering 49.5 per cent of the votes, while the opposition’s joint candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu secured 44.9 per cent.

In her article about the outcome of the recent Turkish vote, the author, who specialised in Turkey and economics, says that it was not the polls alone that convinced Turkey’s opposition that it had a chance to topple Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s two-decade reign, but there were several good reasons for the opposition to win as an antidote to one-man rule.

“There were plenty of good reasons for the opposition to be confident of putting an end to their 21-year losing streak. The economy’s slow-motion crisis has lately achieved an excruciating clip, thanks to eccentric policies indelibly associated with the president – so who better to spearhead a return to orthodoxy than Kılıçdaroğlu, a challenger who, though 74 years old, closely resembles a young Friedrich Hayek*? Against a backdrop of inflation hovering around 50 per cent, it would have been crazy not to believe.”

While saying that the unification of so many opposition parties around a single challenger could and should have made a difference, Finkel recalls that some of the factors that commentators only talked about after the elections, such as the government’s dismantlement of the media, and the fact that in times of crisis, people turn to a strong man, overlooking his complicity in their fates were there all along.

“At next Sunday’s run-off Kılıçdaroğlu somehow has to target the 5 per cent of voters who came out for the ultranationalist third candidate (Sinan Oğan) without jeopardising his informal alliance with the predominantly Kurdish party of the left,” she writes, stressing that in the first round, Kılıçdaroğlu received his highest shares of the vote not in his own party’s secular western but in the southeastern Kurdish provinces where the pro-Kurdish Green Left Party’s voters are in the majority.

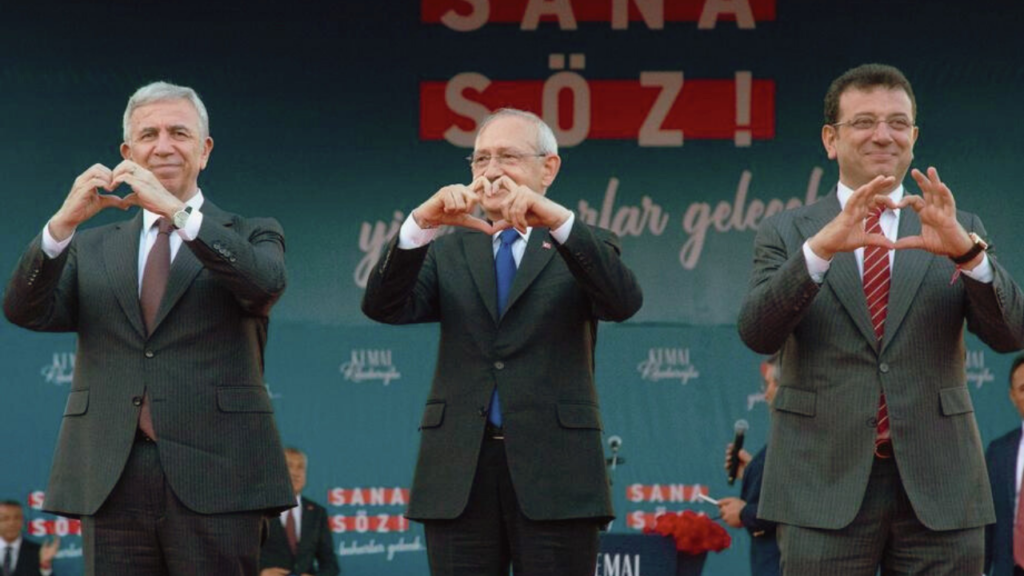

“His first major post-election broadcast underlined his difficult position. He chose to emphasise border security, voicing a coded promise to expel millions of Syrian refugees. Before the election, the opposition’s informal symbol had been a heart formed by two joined hands.”

The revelation of some of the irregularities was unlikely to play such an important role in the run-off vote, Finkel believes. “No one needs to fiddle the numbers when morale on one side is this low,” she argues.

Finkel also questions the statements of observers that the elections in Turkey were free but not fair. The author argues that the really high turnout of 89 per cent might not be an indication of democratic and free elections, but rather proof of the fact that in a country where power was so centralised, the stakes around elections were far too high.